Russian Roulette

a "Russian Roulette" I threw together real quick

Ryszard Tobys of Poland holds the Guinness World Record for the world’s largest working revolver.

*Did you notice his enthusiastic excitement and happiness over getting that award?

Because most of the parts are handmade, the massive replica of the Remington model 1859 took almost 2,500 hours to build.

The six-shot revolver uses 136 gram (or 2,099 grain) projectiles and claims to have “great accuracy” at ranges up to 50 meters.

In Mikhail Lermontov's "The Fatalist" (1840), one of five novellas comprising his A Hero of Our Time, a minor character places a gun with an unknown number of bullets to his head, pulls the trigger and survives. However, the term "Russian roulette" does not appear in the story.

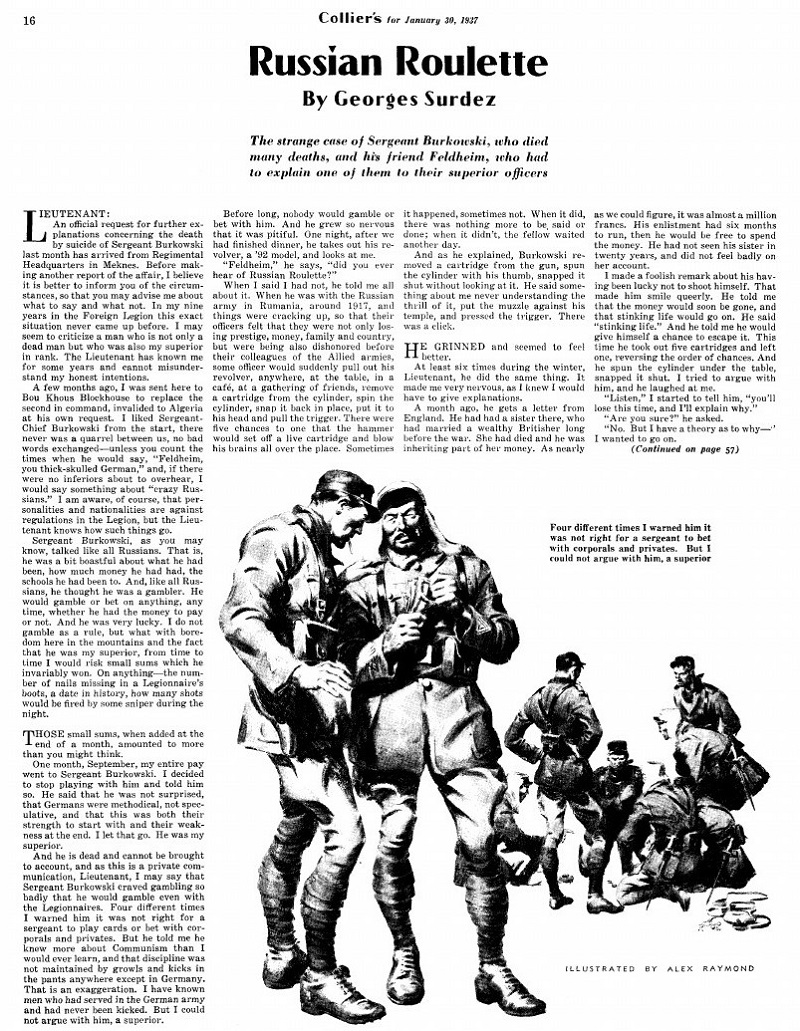

The term "Russian roulette" was possibly first used in an eponymous 1937 short story by Georges Surdez. However, the story describes using a gun with one empty chamber out of six, instead of five empty chambers out of six:

- "'Did you ever hear of Russian Roulette?' ... with the Russian army in Romania, around 1917... some officer would suddenly pull out his revolver, anywhere, at the table, remove a cartridge from the cylinder, spin the cylinder, snap it back in place, put it to his head and pull the trigger. There were five chances to one that the hammer would set off a live cartridge and blow his brains all over the place."

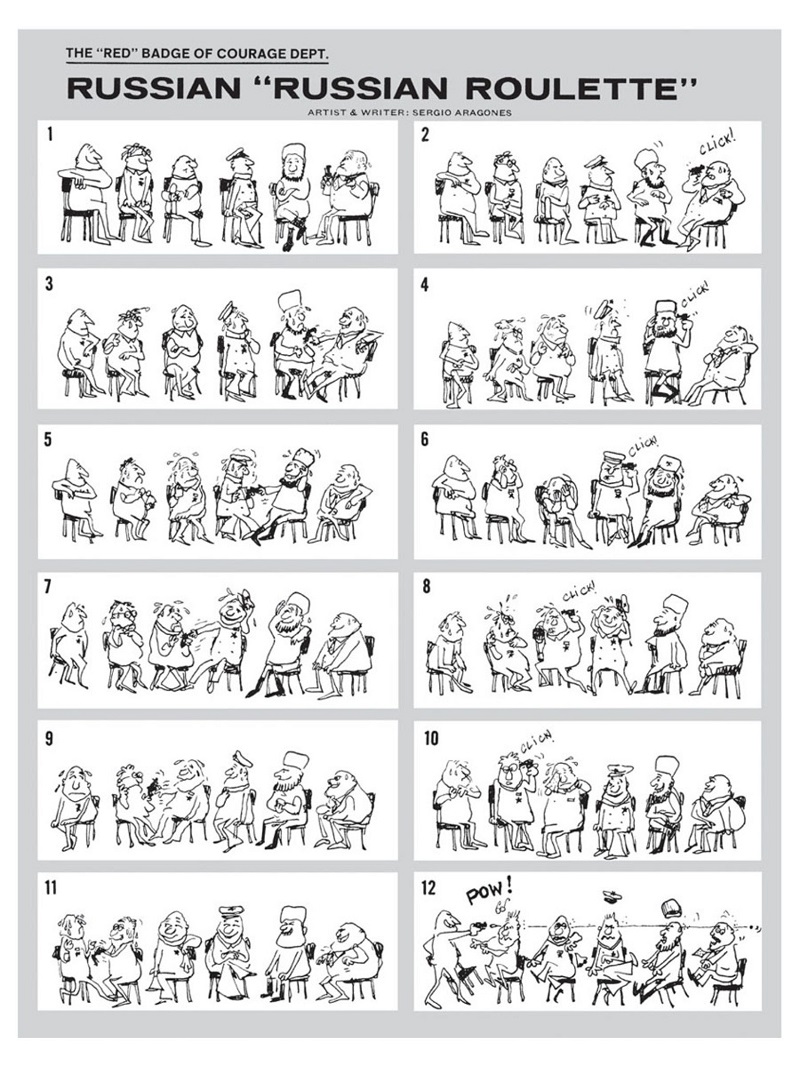

In 1963, MAD Magazine published the Sergio Aragonés cartoon Russian "Russian Roulette", in which six men play the game without spinning the chamber of a revolver between turns. When the last (and doomed) man gets the gun he fires it back through the heads of the other five.

System of a Down also mentions Russian Roulette in their song Sugar:

"I play Russian roulette every day, It's a man's sport.. with a bullet called life".

In the "Tales From The Crypt" episode "Cutting Cards," Russian roulette is one of the games played.

- On December 25, 1954, the American blues musician Johnny Ace killed himself in Texas, after a gun he pointed at his own head discharged. A report in The Washington Post attributed this to Russian roulette.

- Graham Greene relates in his first autobiography, A Sort of Life (1971), that he played Russian roulette, alone, a few times as a teenager.

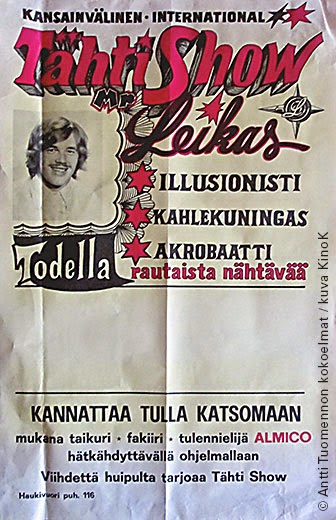

- In 1976, Finnish magician Aimo Leikas killed himself in front of a crowd while performing his Russian roulette act. He had been performing the act for about a year, selecting six bullets from a box of assorted live and dummy ammunition.

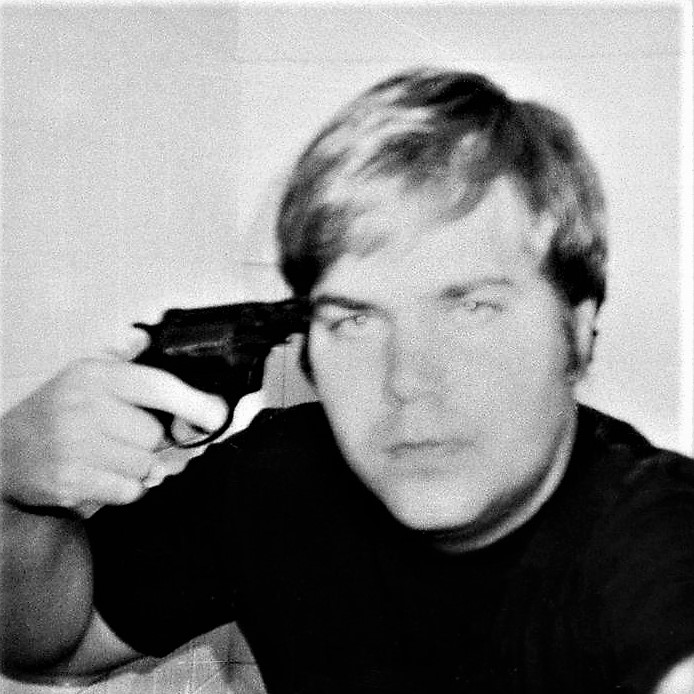

- John Hinckley, Jr., who attempted to assassinate President Ronald Reagan in 1981, was known to have played Russian roulette, alone, on two occasions. Hinckley also took a picture of himself in 1980, pointing a gun at his head.

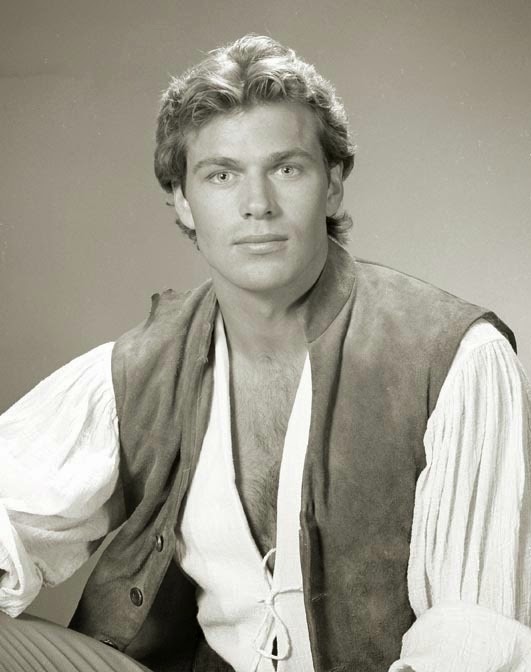

- On October 12, 1984, while waiting on filming to resume on Cover Up (1985), actor Jon-Erik Hexum played Russian roulette with a .44 Magnum revolver loaded with a blank. The gunshot fractured his skull and caused massive cerebral hemorrhaging when bone fragments were forced through his brain. He was rushed to Beverly Hills Medical Center, where he was pronounced brain dead.

- PBS claims that William Shockley, co-inventor of the transistor and winner of the Nobel Prize for Physics, had attempted suicide by playing a solo game of Russian roulette.

- On October 5, 2003, UK Psychologist and Magician, Derren Brown played a live version of Russian Roulette. It was broadcast late in the evening from the Isle of Jersey (where the possession of firearms is allowed) The format followed Brown and a member of the public as he played a solo game. The member of the public selected a chamber at will, and loaded a bullet. He then closed the gun and sat behind a protective screen. Brown played the game by guessing through psychology and reading which chamber it was loaded. Brown succeeded and proved it by firing into a sandbag.

- Evan Hunter's short story "The Last Spin" takes place in a small basement. Tigo and Danny, two members of opposing gangs, are forced to play a game of Russian roulette to settle disagreements between their gangs.

- The BBC program Who Do You Think You Are?, on 13 September 2010, featured the actor Alan Cumming investigating his grandfather Tommy Darling, who he discovered had died playing Russian roulette while serving as a police officer in British Malaya. The family had previously believed he had died accidentally while cleaning his gun.

- On June 11, 2016, MMA fighter Ivan "JP" Cole apparently killed himself by playing Russian roulette.

- "In the episode "Venezuela" of Banged Up Abroad, James Miles and Paul Loseby voice their utter shock and horror when they discover the prisoners playing Russian roulette. After having his appeal refused and facing a 10-year sentence, as well as due to the harshness of the prison life and complete lack of self-esteem, James eventually participated in the game."

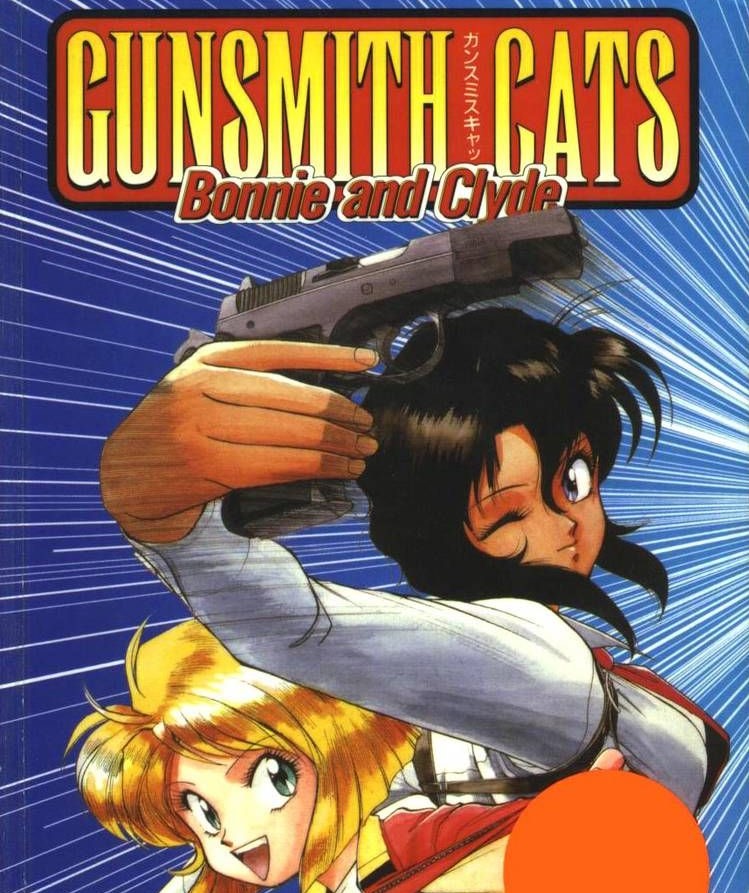

In the first chapter of the manga series Gunsmith Cats, the main character interrogates an intruder by playing a version of Russian Roulette where she pulls the trigger five times, bragging about her ability to time her spin so she knows where to stop.

bragging about her ability to time her spin so she knows where to stop.

- In the 1986 movie Crawlspace, the main character used Russian Roulette to determine his own fate.

Commonwealth v. Malone, 47 A.2d 445 (1946), was a case decided by the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania that affirmed the conviction of a teenager for second degree murder. The teenagers had played a modified version of Russian roulette called Russian Poker, in which they took turns aiming and pulling the trigger of a revolver at each other, rather than at their own heads. Therefore without an intent to kill or harm, Malone had pointed the gun at his friend's head and pulled the trigger, killing him. However, the court ruled that "When an individual commits an act of gross recklessness without regard to the probability that death to another is likely to result, that individual exhibits the state of mind required to uphold a conviction of manslaughter even if the individual did not intend for death to ensue."

The case is often used to exemplify depraved-heart murder - that is, cases where there is such recklessness and indifference to life and risk of death as to fulfill the mens rea for murder despite the fact that the killing of the specific victim was unintentional. It has not yet been established whether simply participating in a game of Russian roulette in which another participant kills himself by his own hand could constitute manslaughter or some lesser form of conspiracy or homicide for others involved who survived.

According to the defense, Malone loaded the gun chamber adjacent to the firing chamber and did not expect the gun to go off when he pulled the trigger.

Decision: The court used common law analysis to determine that a game of Russian roulette evinced malice and recklessness towards a very serious risk, thus fulfilling the mens rea required for depraved heart murder despite the fact that the killing of the specific victim was unintentional.

Anthony Santiago Cadiz Jr was nineteen-years-old when he blew his head apart with a .357 magnum revolver. His mother, Melissa Vasquez, lost her son just when she thought she had triumphed over criminal elements in their Hispanic  neighbourhood of inner city Springfield, Massachusetts, in a tug of war for his soul.

neighbourhood of inner city Springfield, Massachusetts, in a tug of war for his soul.

They ended up throwing him out, but eventually he moved into an apartment on East High Street with a friend and the excitement at his new independent life led to a reconciliation. On the evening of February 12th Anthony rang his father to say he had things to discuss and would come by to see him.

But he never arrived.. Later that evening a police officer rang Cadiz sr. to tell him his son was dead. Anthony had been sitting in his apartment with a group of friends, all were drinking alcohol along with suspected drug use, said the officer, but those who were there that night denied the rumours of drug use. Something illegal in the apartment that was undeniable is an unlicensed .357 magnum revolver.

As the group talked and joked Anthony cracked open the revolver’s cylinder, tipped six bullets out of the gun and replaced one. He pushed the cylinder back into the gun, spun it and put the gun to his head...

He pulled the trigger and the hammer fell on an empty chamber. A friend told Anthony to stop messing around and reached for the gun. Laughing, Anthony Santiago Cadiz Jr pulled the trigger again. This time the gun went off.

A reporter for the New Hampshire Union Leader tracked down Anthony’s father to get his reaction:

‘The last couple of weeks he was OK,’ he said. ‘He was happy, excited. He had his place and then he called me last night and then he’s dead.’

You have probably not sat around a cheap apartment in Manchester, Massachusetts drinking and talking, and watched a friend shoot himself in the head.

But chances are you know about Russian Roulette.

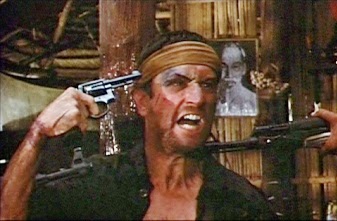

Just hearing the words bring images to the mind. Probably from a movie. Probably The Deer Hunter and the man with the gun to his head, Robert DeNiro, one of the greatest American actors of all-time and one of the most intense. Few other actors would tease open sores on their face to bring reality to their portrayal of a young glue sniffer in Bloody Mama or put on sixty pounds to bring 1950’s boxing champion Jake LaMotta to life. The Deer Hunter was made in 1978 but the image of DeNiro with a red bandana wrapped around his head and a revolver in his hand is still iconic.

You might know that blues crooner Johnny Ace shot himself dead backstage at a 1954 Christmas Day gig. Literary types will remember that Graham Greene, author of Brighton Rock and The Third Man, confessed to playing Russian Roulette as a troubled Oxford student in the mid-1920s. Or that a character in Steven Millhauser’s 1977 novel Portrait Of A Romantic dies playing it.

How many people die playing?

Russian Roulette has killed over 1,000 people in the last century. The youngest was five-years-old and the eldest seventy-eight.

Investigating Russian roulette is living a real life detective story with hundreds of corpses and thousands of smoking guns. Anthony Cadiz’s death to DeNiro’s big scene are all links in a chain of gunshots, movies, metaphors and literature that stretches back to the First World War

It was carried like a virus out of the Siberian steppes, witnessed by British mercenaries in provincial Russian towns, and reached western Europe in the aftermath of the Revolution as monarchist exiles fled the Bolsheviks. In France it infected the Surrealists and dosed Graham Greene in Oxford. The death toll took a massive leap when Swiss born writer Georges Arthur Surdez wrote a fictional story about the practice for an American magazine. The contagion spread.

In the USA it found the environmental factors to flourish: easy access to firearms, alcohol, drugs, a large teenage population, and a popular culture that glamourised the practice. It stayed in America for forty years and claimed many more victims before The Deer Hunter acted as needle to inject the poison back into Europe and across the world.

Now English magicians play it live on television and Turkish teenagers blow their brains out at school. Australian gangster Mark ‘Chopper’ Read claimed to have played it for money in a Footscray pool hall.

If you are reading this then you’re smart enough not to put a gun with one bullet to your head and pull the trigger. Anthony’s impulsive game of self-murder will not resonate with you. Make sure it stays that way.

Welcome to the world of drunken teenagers, suicidal Polish officers, Samuel Colt’s legacy and the kind of people who care so little about life they put a partly loaded gun to their head and pull the trigger. This is the history of Russian Roulette.

Texan winters are unpredictable. Rain turns the state into a soggy mess one day then blazing sun bakes it hard the next. This changeability is especially pronounced in the state capital of Austin.

On Saturday 8 January 1938 they had their usual dose of fickle climate. The sun shone intermittently through the day but by late afternoon grey skies ruled and a chill wind chased commuters out of the downtown business district into the suburbs. In an upscale part of town a young man called Thomas H Markley jnr celebrated his twenty-first birthday with a gang of college friends outside his parents’ house.

He had a case of beer and a revolver to keep him warm.

Texas oil revenue sheltered Markley’s hometown from the worst of the financial depression that blighted America in the thirties but Austin had not completely escaped the country’s economic melt down. A few miles past the city limits hundreds of men lived in government work camps digging ditches with President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal programme.

No danger of government handouts for the birthday boy. A recent graduate of the 200 acres of red terracotta roofs and Spanish architecture that made up the University of Texas campus in Austin’s centre, Thomas jnr had plans for his future. He was the brains behind new photo-magazine The Drag, named after a strip of shops and bars on Guadalupe Street, aimed at students and due to hit stores Monday.

By evening he and his friends had worked their way through the beer. Texas was a gun loving state where no home was complete without a hunting rifle and a handgun. None of Markley’s friends were concerned when he produced a revolver. They only protested when he asked everyone to watch as he played a game he called ‘Russian Roulette’.

Markley told them he knew what he was doing, put one bullet in the gun, spun the cylinder and put the revolver to his head. As his friends watched he blew a hole in his skull and fell twitching on the grass. His parents buried him in Oakwood cemetery near the University.

He was the first victim of Russian Roulette in America.

Seven months to the day later another twenty-one-year-old Texan, this time in the crowded metropolis of Houston, tried the same trick. Paul Grasso sat in his car joking around with a revolver late at night. Like Markley he put one bullet in the gun and manipulated the cylinder. His friend George Tillota warned him to be careful.

‘Watch – I’ll show you it won’t go off,’ Grasso said.

He held the gun pointed backwards towards him at arms length, thumb on the trigger, and squeezed. The hammer came down on the chamber holding the bullet and Grasso bounced off his seat into the steering wheel, spraying blood from a massive head wound.

Why did two young men die like this? Leading newspaper for America’s southern states the Dallas Morning News had no idea. The paper’s hacks failed to uncover the origins of Russian Roulette (‘a gruesome game‘) or the reason for its popularity among young Texan men. The best they could do was assure readers that Markley and Grasso’s deaths were not suicide. Markley wrongly believed the weight of the single bullet in the revolver would roll it to the bottom of the cylinder when spun. Grasso tried to set his revolver so an empty chamber rotated under the hammer.

Four months later the Lone Star state lost exclusive rights to Russian Roulette.

In 1938 only heavyweights like the Wall Street Journal or the New York Times were available nationwide and most Americans read the regional press. It would have been a sharp eyed southerner who spotted the headline ‘Boy’s Triple Death Gamble Told By Chum At Inquest’ in 22 November edition of the Los Angeles Times and figured the gun game had spread to another state.

Sixteen-year-old Richard V Brady died at his parents’ Los Angeles home as he demonstrated Russian Roulette to a thirteen-year-old school friend.

‘After school we went to Richard’s home,’ the teenage witness told the inquest. ‘Richard got his father’s gun and put a shell in it. He twirled the cylinder, put it against his head and pulled the trigger. It didn’t go off. Richard dared me to do it but I wouldn’t. Then he did it a second time and the gun just clicked. But the third time he pulled the trigger the gun went off.’

The Times had a better research department than the Dallas Morning News and was able to give its readers a brief history of Russian Roulette, straight from the inquest. The anonymous staff reporter assigned to the story explained it was the invention of fatalistic Russian soldiers – ‘maddened by starvation and fear of death’ – during the last World War. If the Russian survived, he won. No journalists connected Russian Roulette with Georges Surdez, the Swiss pulp fiction writer who named it.

Before Surdez’s story appeared in Collier’s 30 January 1937 issue no occurrences of Russian Roulette, name or practice, were reported in America. Then in the late 1930s four young men died in three states – Markley and Grasso in Texas, Brady in California, and a fourth youth whose fatal gamble with Russian Roulette in July 1939 got a few lines in the Nevada State Journal.

Russian Roulette existed as an anonymous gun game for twenty years before Surdez settled down at his typewriter to write his short story about the French Foreign Legion. It was reported in Russia, Poland, France, and England. It’s a fair deduction that Surdez was the plague carrier who introduced it to America. He was lucky that by the time people started dying the practice had sunk deep enough into the culture that no-one remembered he had been the source.

Over the next seventy years 1,000 people would die. Something about the United States made it the perfect breeding ground for a suicidal gun game.

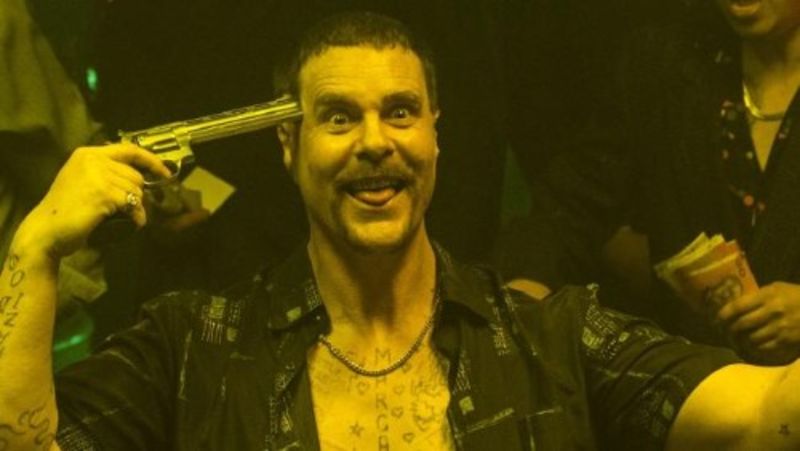

Chopper forces a reporter to play Russian Roulette (below) at 00:10:08

From above, the city of Melbourne looks like a bird of prey on the attack. Its wings stretch up into northern suburbs and its beak bears down to snatch a kill from Port Phillip Bay, the huge inland expanse of water on which the city sits. The bird’s beady eye is located in a grid of factories and Victorian houses known as Footscray.

Until the Second World War this area was the epitome of joyless working-class Australian suburbia. Pubs shut at six and restaurants risked a visit from the police if they served wine after eight. Except for a weekly trip to Oval Centre for the footy, Footscray’s inhabitants stayed home and minded their own business.

Those locals would not recognise Footscray today. The grey suburb has been transformed into a colourful district for young professionals attracted by cheap rents and a short commute to Melbourne’s centre. Coffee shops and art galleries thrive on the main streets. Restaurants and bars do good business.

The make over was achieved with immigration. In the 1950s and ‘60s a wave of European immigrants, most Greeks and Albanians, washed up in Melbourne and discovered working class Footscray was one of the few places they could afford to live. Their presence lit the touch paper on the suburb’s regeneration, although the gunpowder only really started fizzing when Vietnamese refuges from Communism – the ‘Boat People’ – settled in the seventies. Soon Footscray boasted noodle bars alongside mosques, and mah-jong parlours opposite tavernas. It took Melbourne’s middle classes another twenty years to wake up to the vibrant and cheap neighbourhood right under their noses.

Footscray is now the poster child for multicultural Australia but back in 1987 it was an edgier place run by Vietnamese and Albanian gangsters. The two groups usually kept a wary distance but on one occasion they dropped their suspicions long enough to co-operate on a money making venture. The event was also a historic first, although not one that will ever make it onto the Footscray council website. Under gangster patronage the suburb hosted the only recorded game of Russian Roulette in which players were paid to risk their lives in front of an audience.

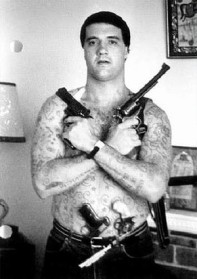

The key man in the event was Mark Brandon ‘Chopper’ Read, six foot two of scarred Australian muscle held together by prison tattoos and a handlebar moustache. Brought up in the tough northern Melbourne suburbs, Read’s mother was a fanatical Seventh Day Adventist who beat him on any pretext and his father a gun-loving hard drinker. After his mother left when he was a teenager Read was free to run with street gangs where everyone carried a knife in their belt and a pool ball in a sock. He mixed with underage prostitutes and gangsters. The police opened a dossier on him that would eventually be the size of a phone book. First arrested at the age of 17, he would spend only 13 months outside prison in the next twenty years.

In 1977 a psychiatrist at Pentridge Prison noted the twenty-three-year-old’s high intelligence but declared him insane. It was the third time Read had received the diagnosis. Read dismissed the first assessment, done at fifteen, because it was done by a Seventh Day Adventist psychiatrist friend of his mother. He had less to say about the second at age nineteen.

‘Yeah, they probably had a reason to certify me then‘.

‘Yeah, they probably had a reason to certify me then‘.

In Pentridge prison he formed the Overcoat Gang – so called because they wore coats all year round to hide their armoury of machetes and clubs. They were all as crazy as their leader.

‘I used to try and recruit people from within the prison system who’d all been certified mentally insane,’ said Read.

His misfit army went to war with the Painters & Dockers, the imprisoned leaders of a powerful Melbourne Labour Union whose activities extended into crime. Read wanted to be top dog in Pentridge’s H Division. Prisoners bashed and stabbed each other while the guards looked on. At the height of the gang war Read proposed a cell block uprising. His followers would take the guards hostage then ice pick their enemies in the spine.

‘This idea was the maddest idea ever put together […],’ said Read. ‘It would have worked too. Because back then I didn’t care how long I did in jail, I didn’t care about the consequences.’

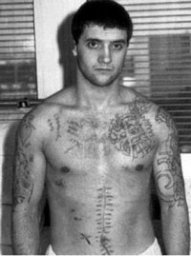

His gang mates did care and tried to kill him to prevent the plan going into action. Chopper took a mess of stab wounds to the stomach and lost several feet of intestine, but survived. The next day he split his stitches doing press-ups in the infirmary.

After the attack Read had no friends and a cell block full of enemies. The governor refused to transfer him to the safety of another block so Read sawed off his own ears with a razor blade. He got transferred to a psychiatric ward. The nickname Chopper may have come from that incident or perhaps his later habit of cutting off the toes of drug dealers to make them talk. Or perhaps from the cartoon bulldog in Hannah Barbara’s Yakky Doodle who always protected his friends.

‘Why let the truth get in the way of a good yarn?‘ as Read said.

He got out of prison in the early 1980s. Now Mr Read to his Probation Officer, Mark to his dad, and Uncle Chop Chop to very good friends, he moved up the criminal career ladder. He left behind street fights and petty robberies to become a stand over man – a criminal who extorts and robs other criminals, mostly dealers and pimps. Reed used a blowtorch, a pair of pliers and a soundproofed cellar in a friend’s pub to make his victims give up the money. Sometimes he made house calls.

‘They used to say to me “how the hell did you find out where I lived?” Drug dealers, they used to spend a fortune on security right? It was the only house on the street with spotlights that come on all night long with a sixteen foot high fence […] You drive down the street with slum houses and you got one house there with ornate Italian wrought iron work, spotlights, guard dogs, you know. Where does the drug dealer live?‘

Predictably he was soon back inside. Free again in 1987, Read found himself outside a Footscray pool hall with a .44 Ruger Black Hawk revolver at the invitation of some Albanian gangsters with contacts to Vietnamese organised crime. Friction between the two groups had resulted in a challenge: one man from each side to play Russian Roulette while bets were laid on the outcome. The Albanians did not really want to play but were unwilling to lose face. They looked for a man who would take part on their behalf.

The Albanians’ offered Read AUS$6,000 if he survived. They were pushing at an open door. The stand over man had recently adopted the tactic of strapping a stick of dynamite to his chest and threatening to blow up himself and his victim if they did not cough up the cash.

The Vietnamese began to arrive in Australia in the late 1970s fleeing their Communist homeland in flotillas of overloaded, leaky fishing boats. By 1987 over 100,000 had washed up on Australia’s shores. Often they faced an unfriendly welcome. For most of the twentieth century a ‘White Australia’ immigration policy had been in place, blocking any faces that might spoil the atmosphere of British suburbia set down among the kangaroos and Eucalyptus trees. When the policy was lifted in 1973 and new ethnic groups, such as Turks and Chinese, began to arrive in Australia the white population greeted them with hostility and sometimes violence. Newly opened Vietnamese restaurants frequently got a brick through the window.

Not all Vietnamese immigrants were angels. There were more than enough gangsters and tough guys in the diaspora to cause problems for the police. By the mid-80s Vietnamese criminal gangs were becoming a concern.

‘Criminal gangs in the Vietnamese community are increasingly heavily armed,’ announced a Police report, ‘and are moving into drugs and gambling, establishing links with Australian crime figures, and becoming involved in standover rackets in their own community.’

The Albanians were immigrants of a less recent vintage. They did not gamble as much as the Vietnamese, although they probably smoked more, but they liked a flutter and a bit of blood. The east European immigrants had carved out a niche for themselves in the Melbourne underworld since arriving in two waves, first in the 1920s and then after the Second World War, when Australia accepted a number of refugees fleeing Communism. Settled in Footscray for thirty years and deeply involved in local drugs and protection rackets the Albanians watched the Vietnamese new arrivals with suspicion. Tensions mounted.

Why did the Vietnamese suggest Russian Roulette to settle things? According to Read they were fans of The Deer Hunter movie. Released at the tail end of 1978 Michael Cinimo‘s three hour Hollywood epic won five Oscars and cleaned up at the box office, although not without controversy.

‘For three years there was virtual silence [on the Vietnam War],’ wrote left-wing Australian journalist John Pilger. ‘Then Hollywood sensed that a lot of money could be made with a movie that appealed directly to those racist instincts that cause wars and that allowed the Vietnam war to endure for so long—a movie that reincarnated the Batman-jawed Caucasian warrior, that presented the Vietnamese as Oriental brutes and dolts‘.

Pilger and other critics were especially appalled by a scene in which the main characters, all Americans, are forced to play Russian Roulette by their sadistic Vietcong guards while a photograph of Ho Chi Minh looks on. The critics claimed Russian Roulette had never been played in the Vietnam war. Cimino and others claimed it had. Or that even if it had not the game was a metaphor for the arbitrary distribution of death in war. The director was reluctant to admit the Russian Roulette angle came from the original script he inherited that had nothing to do with Vietnam. Most viewers ignored the arguments and perched on the edge of their seats as a grim faced Vietcong officer (actually a Thai driver for the film crew called Somsak Sengvilai who caught the attention of Michael Cinimo) spun the revolver cylinder and handed it to Robert DeNiro.

It did not bother the Vietnamese gangsters in Footscray that leftists thought Russian Roulette was a slur on their country. Melbourne Vietnamese had spent the early 1980s fighting not only racist skinheads but also far-left thugs unhappy with the immigrants’ anti-Communism. They did not care about Pilger and co’s criticisms. The Vietnamese thought it would be a kick to see the game in real life. The Albanians thought the same. They just needed someone crazy enough to play it.

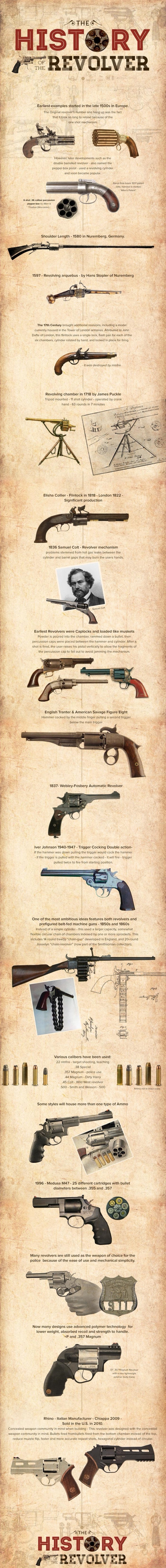

A quick lesson in firearm construction. Almost all revolvers consist of a frame, a trigger on the underside of the frame, a hammer at the top, and a cylinder which revolves within the frame and contains six chambers each holding one bullet.

When the trigger is pulled the cylinder moves the next chamber under the hammer, simultaneously raising and dropping the hammer – if it is double action as most modern revolvers are. If the gun is already cocked then pulling the trigger just drops the hammer. The tip of the hammer hits the firing cap at the back of the bullet case. The cordite ignites and the explosive pressure forces the bullet out of the case (which remains in the chamber) and out of the gun through the barrel.

To play Russian Roulette you place one bullet in the cylinder. The cylinder can be swung out of the gun to do this but in some older models the cylinder is lodged in the frame and the bullet must be slipped in through a loading gate. Next spin the cylinder, either outside or inside the frame. If outside snap the cylinder back into the frame. Put the gun to your head and pull the trigger.

Reed had a theory about Russian Roulette.

‘I made sure I had a little advantage no-one else knew about. I knew my gun was perfectly balanced, so that if I put a slug in at the top and spun it the right way and snapped the cylinder back, it would snap back with the slug at the bottom. Well, 19 times out of 20, anyway, which is good enough odds for me.’

Read’s theory is absolutely wrong but he went into the pool hall convinced he had an advantage. He had played Russian Roulette before a few times, drunk at parties, holding two fingers up to Death.

Inside, the hall was as smoke stained yellow as a diseased lung. Read’s entrance made a big impression on the waiting gangsters. At a time when the average Australian male still had a seventies bouffant hairdo and wing collar shirts, Read had close cropped hair and no ears. He stripped to the waist, revealing a mosaic of prison tattoos (stars, swirls, hearts, girl’s names, ‘BUSHIDO’) and a second pistol in his belt. He insisted on using his own Black Hawk revolver. To prove the game was for real a Vietnamese test fired the gun into a stack of telephone directories. The sound of the shot crashed around the pool hall. Cordite smoke cut through the thick stink of cigarettes.

Inside, the hall was as smoke stained yellow as a diseased lung. Read’s entrance made a big impression on the waiting gangsters. At a time when the average Australian male still had a seventies bouffant hairdo and wing collar shirts, Read had close cropped hair and no ears. He stripped to the waist, revealing a mosaic of prison tattoos (stars, swirls, hearts, girl’s names, ‘BUSHIDO’) and a second pistol in his belt. He insisted on using his own Black Hawk revolver. To prove the game was for real a Vietnamese test fired the gun into a stack of telephone directories. The sound of the shot crashed around the pool hall. Cordite smoke cut through the thick stink of cigarettes.

‘To do well in the game you have to be willing to die,’ said Read. ‘You had to will yourself into a state of mind where you were prepared to die. If you play just to make money or show how much guts you have you will lose in the end. You have to be mentally prepared for death even before you walk into the game.’

The Vietnamese had arranged another player, one of their own, to face Read. The .44 revolver was handed to the Australian. A bullet was placed on the table between the players. Once the gun was loaded each player would take turns spinning the cylinder and putting the gun to their heads. Read looked at the ring of faces, the cigarette smoke, the money changing hands. He slid the bullet into the cylinder, spun it and pushed it back into the gun frame. He aimed the barrel at his temple. Then he grinned a mouthful of gold teeth and pulled the trigger.

No-one knows exactly when and where the original roulette wheel was invented. The French like to believe it was invented in the seventeenth century by mathematician Blaise Pascal as an off-shoot of his quest to find a perpetual motion machine. All the other putative inventors are anonymous (a ‘Benedictine monk’ and a ‘Hindu astrologer’ are among those put forward) so Pascal, a colourful and relatively well-known figure, tends to get the credit. The mathematician was, after all, such an enthusiast for games of chance that he only believed in God because it gave better long term odds than atheism.

The Roulette wheel has gone through many permutations over the years but the basics have remained the same since Pascal, or whoever, first decided to fling a ball around a coliseum-shaped structure the size of a bicycle wheel and see where it ended up. These days the Roulette wheel is divided into 36 numbered compartments, alternating red and black, each separated from its neighbour by a slight ridge. Gamblers can bet on a single number coming up or, for lesser returns, on increasingly large groups of numbers up to odd or even, red or black.

As a game of pure chance roulette is tough to beat at the best of times but when it took off in the eighteenth century French gambling czars Francois and Louis Blanc added a zero to the wheel to increase the house odds. Players can bet on the zero itself but not include it in larger groups of numbers. It gave the gambling house an advantage of 2.7% but that proved insufficient for greedy casino owners and when roulette made it to America later in the century they added a second zero (often in the patriotic form of an eagle) to give an even greater edge.

‘It is impossible to beat a roulette table unless you steal money off it,’ said Albert Einstein.

The only connection between Russian Roulette and Pascal’s game is the name. The anonymous revolver practice had been around for twenty years before a Swiss immigrant in Brooklyn, New York christened it for a 1937 short story he was writing. The bronze and lead cartridge spinning in the revolver cylinder reminded Georges Surdez of a ball rattling round a roulette wheel.

If the average man or woman on the streets of Melbourne or Hanoi has heard about ‘Chopper’ Read’s activities in Footscray they assume it is a typical example of Russian Roulette – the dark smoky room, money on the table, bets on the outcome, gangsters to haul away the bodies. It is an image that owes more to ‘The Deer Hunter’ than reality. It is very hard to turn Russian Roulette into a gambling game. There are no rules and no reason behind it. And who, apart from a mentally unbalanced Australian gangster, is going to risk putting a bullet in their own head for money?

An American called Anson Paape was one of the few who tried to make the practice into a game and is now doing seventy-five years in an Illinois prison. Paape was a thirty-eight-year-old occasionally employed tree trimmer and full-time drunk whose house in the quiet Elmhurst suburb of Chicago had become a hang out for local teens who liked a beer. On 8 July 2004 Michael Murray celebrated his eighteenth birthday at the house with a few friends. As the beers went down Paape produced an unloaded .44 revolver and distributed bullets and cards. They were going to play poker, he announced, and the winner got to load a single bullet in the gun and fire at the person sitting next to them.

Paape was drunk and the rules kept changing before the game even started so the teens thought he was kidding. When Murray won the first hand Paape insisted he load up the revolver. Murray refused so Paape did it for him then pointed the gun at the birthday boy. Murray tried to bat away the barrel but Paape told him ‘it’s my gun, it’s my house, I’ll do it‘ and pulled the trigger. The gun went off and blasted a hole in Murray’s forehead.

When the ambulance crew got there Murray was a bloody heap on the floor, the teens had fled, and Paape was on the run. The police got him two days later. He claimed it was an accident and his lawyer pushed for manslaughter (‘it was an innocent, idiotic birthday game‘) but the courts found Paape guilty of first degree murder.

Back in the Footscray pool hall Mark ‘Chopper’ Read pulled the trigger on his Blackhawk .44 revolver. The hammer came down on an empty chamber. Money changed hands.

Now it was the opponent’s turn. The gun passed to him. One bullet went in the revolver, the cylinder was spun and the barrel went to his head. The Vietnamese crowded around him, a mistake in Chopper’s eyes as a.44 bullet would plough through a roomful of skulls before it slowed down. Click. More money was thrown down on the table. Now it was his turn again. Convinced the odds were in his favour, Chopper spun the cylinder and carried on.

He survived. His opponent bailed out. Read got a ‘good earn’. He returned to the pool hall on several occasions playing against an opponent (‘no-one ever went more than three spins against me’) or on his own. Eventually he called it quits.

Chopper went back to prison shortly after Footscray for his stand over activities. While inside he corresponded with a pair Melbourne crime reporters about his life in the underworld. The letters were sharp, funny, unrepentant, and violent. Read had nothing but time on his hands. The pair edited the letters down and published them.

‘Chopper’ came out in 1990 and was an instant success. The locked up stand over man became a media celebrity.

‘A best selling author. And I can’t even spell!’

The fame helped him get out on parole and eleven more Chopper books followed, describing prison wars, torture, friends, enemies and, from Chopper 5 onwards, thinly veiled fictional accounts of other people’s crimes. A film was made starring Eric Bana.

Read went back to jail for a while then retired to Tasmania with wife and child. Backwater life proved too quiet and he moved back to Melbourne and more media celebrity. He even co-authored a board game in which losers got mild electric shots: ‘a bit like Russian Roulette.’

Chopper died on 9 October 2013 from liver cancer, which he blamed on the Hepatitis C he contracted in prison.

‘Look, honestly, I haven’t killed that many people,’ he told a New York Times reporter a few months before his death. ‘Probably about four or seven, depending on how you look at it.’

To date, he and his anonymous Vietnamese opponents are the only people who have voluntarily played Russian Roulette for money. According to Chopper anyway. Not everyone believes his stories. But if you can’t trust a toe-cutting, certified mentally insane ex-con, who can you trust?

Test Your Luck. Don't play them in order, 1 to 6, choose any one of them in your own random order until you blow your brains out..

How lucky are you? Play Russian Roulette and find out...