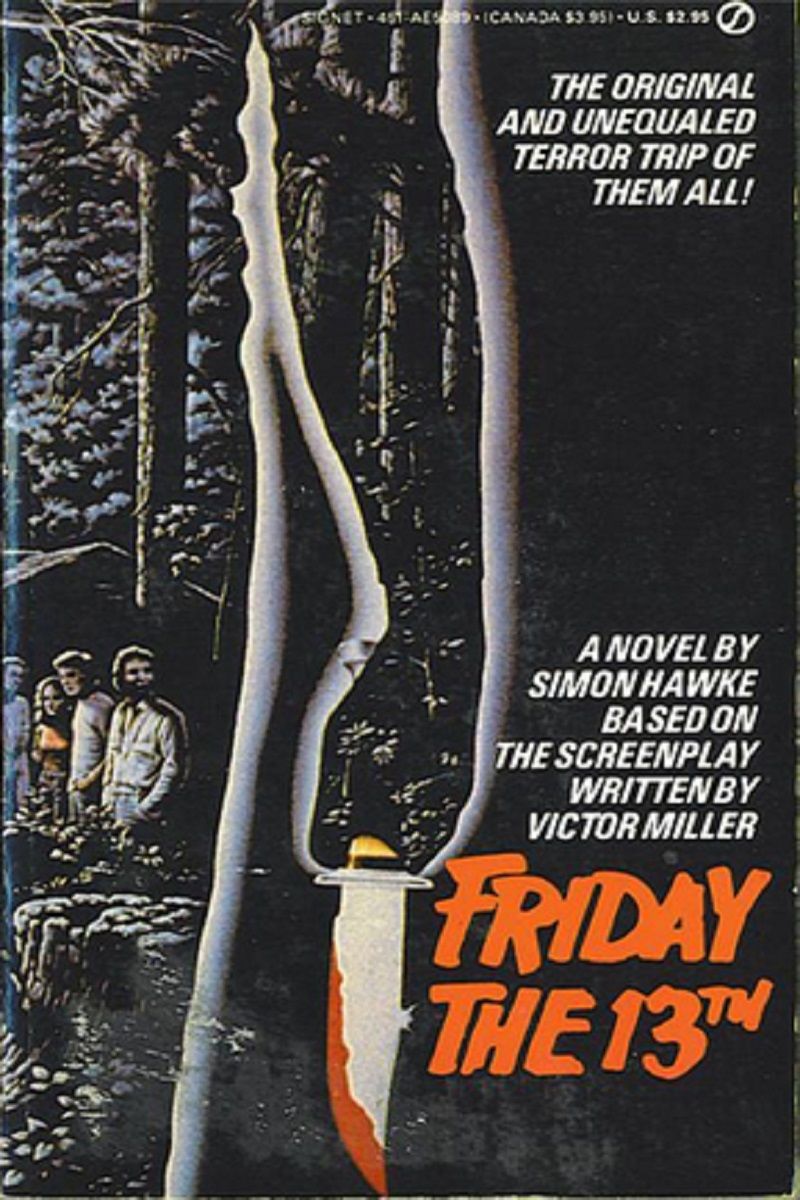

Friday the 13th (Novel)

Prologue

Night is the best time for stories.

It’s dark at night.

What you can’t see in the darkness, you imagine. Sounds you don’t hear in the daytime seem very loud, significant, and ominous. A slight rustling in the bushes, a faint creak on the stair outside the bedroom door. Perhaps it’s only the wind. Perhaps its only the house settling. Perhaps. But sounds at night can be disturbing, noises in the darkness make the imagination see what the naked eye cannot. The imagination feeds on darkness. And it’s hungry at night.

It began, as stories often do, around a campfire on a warm summer night. The time was 1958. The place, Camp Crystal Lake.

Imagine log cabins set back in the trees, picnic tables, a small dock sticking out into a lake surrounded by deep woods, a few rowboats and canoes. There were a thousand places just the same, summer camps run on a shoe-string by small-town-families--the Christy’s in this case, nice people, fond of kids-- places remained locked most of the year, sitting idle, not costing any money except for the few months in summer, when the operating costs were small enough to allow for a little profit.

Crystal Lake wasn’t one of those large, well-financed places with a fleet of paddle boats, a corral full of horses, and a small fortune in sporting-goods equipment. It was just a small family-owned business, cheap to run, cheap to attend. A few cabins nestled in the pine trees on a lake shore near a small town, where lower income families could afford to send their children for a short vacation. Fresh air and outdoor activities for the kids, and a few weeks of peace and quiet for the parents. Not a bad business if you’re not looking for a lot of money.

You hired a few older kids as counselors who doubled as the setup crew, arriving a couple of weeks early to open the camp, turn on the water, and do the little maintenance. In return they got the opportunity to roam in the woods, relax and have a little fun--perhaps even a summertime romance--and you didn’t have to pay them much. It beat the hell out of working as a fry cook at McDonald’s. The counselors took care of the kids when they arrived so you didn’t have to do much. You didn’t really even have to be there. Maybe in the early spring you’d hire a plumber to replace some pipes that had frozen and cracked during the winter. Maybe you’d buy a new rowboat once every few years, some cots and outdoor furniture, all insignificant expenditures. The overhead was low, the time involved was minimal. The operation practically ran itself.

What could go wrong?

The camp had just opened for the summer, but it was going to be a short season. The counselors had spent the day sweeping and cleaning, doing a little bit of carpentry, hauling out the targets for the archery range, storing the supplies. Most of the work was finished. They’d been at it for about a week, and none of them was a stranger anymore. A few had already grown close.

As they sat around the campfire, singing “Michael, Row Your Boat Ashore," Berry hugged his legs and watched Claudette playing the guitar. The two of them were singing an altogether different song, one that did not require any words. Their eyes sent messages.

Claudette finished playing as they sang the last “hallelujah" and wordlessly handed the guitar to one of the other girls, her gaze locked with Barry’s. Barry stood and offered her his hand. She took it, smiling knowingly, and they left the campfire as the group started singing “Hang Down Your Head, Tom Dooley." The sounds of the singing and the guitar receded as they walked through the darkness toward the barn. The crickets, too, were singing in the night.

Claudette hesitated coquettishly at the entrance to the barn, pulling back on Barry’s hand. “Somebody’ll see!" she said.

“No they won’t." Barry tugged her gently by the hand, leading her into the darkness of the barn. He closed the door behind them and flipped on a light. As he turned, Claudette rushed into his arms. Their lips met in a long kiss.

“Does MaryAnn kiss as good as I do?" Claudette asked coyly when they both came up for air.

“How would I know?" Berry said, a bit too quickly."

“Oh, you!"

“Come on."

He took her hand again and led her up the steps into the loft. Claudette picked up a warn woolen blanket. She paused, staring at him uncertainly.

“You said we were special," she said, as if reading from a scrip used by countless young couples before them, performing the necessary motions of the courtship ritual. The unspoken agreement, sealed with knowing gazes and lingering kisses; the token protest; the need for reassurance at the last minute. . .

“I meant everything," Barry said kissing her again to prove it. Perhaps he really did. But it was more likely he didn’t, and she probably knew it, too. The physical need two people felt for one another was only the beginning. Sometimes it was an end in itself, a brief sharing of pleasure, a need mutually fulfilled and selfishly taken. Sometimes it was only a catalyst for something deeper, a bond of real intimacy, but that kind of intimacy only came with time. And although they didn’t know it, neither Barry nor Claudette had much time left.

As they settled down on the blanket they had spread on the floor of the loft, huddling close and holding one another, the barn door downstairs opened slowly. Soft footsteps made little sound as they moved toward the stairs; the music of youthful passion covered the sounds of the measured tread moving stealthily up the steps.

A faint creak, the footsteps hesitated…

But no, they didn’t hear.

“Mmmm," Claudette moaned, and then she stiffened slightly as she felt Barry’s hand fumbling with the zipper on her shorts. “No," she said, catching his hand, but not really fighting.

“Come on," said Barry, his voice plaintive. His lips gently brushed her ear. “A man’s not made of stone."

She giggled.

“Please?"

She sighed, as if with resignation, and released his hand, then her eyes widened as she saw a shadowy figure standing in the darkness at the entrance to the loft.

“Somebody’s there!"

They both sat up in alarm, buttoning up and tucking in, smiling nervously and blushing, feeling embarrassed and self conscious.

“We weren’t doing anything," Barry said quickly. He stood up as the figure in the shadows moved toward them. He smiled guiltily and shrugged. “Hey, really, we were just messin’ around--"

The knife plunged deep into his stomach.

He gasped with pain and shock, doubling over, his hands instinctively going to the wound. The room started to spin and he fell back, landing on a roll of chicken wire, clutching his stomach. Warm blood spurted out between his fingers and ran from the corner of his mouth and life ebbed quickly.

Claudette brought her hands up to her face and screamed.

The killer came toward her.

Claudette backed away, her gaze riveted to the bloody hunting knife. Eight inches of steel streaked with scarlet. She couldn’t tear her eyes away from it. She shook her head, unwilling to believe this was happening.

“No. Please, no!"

She whimpered, darting to the left, then to the right, but the killer followed her motions, blocking off escape, slowly closing the distance between them. She panicked and sought shelter behind a pile of boxes, grabbing them and throwing them, backing away, looking desperately for a way out, but she was cornered. She suddenly felt her back up against the wall and there was no escape. She screamed as she saw the gleaming knife rise and start its swift descent.

It was like a streak of fire across her chest, a burning, incandescent pain more agonizing than anything she had ever felt. The blade bit deeply, ripping through her flesh, sinking in up to the hilt.

It rose again and fell, and rose and fell, and rose and fell, over and over. Claudette wasn’t screaming anymore, but still the killer hacked away, like a runaway machine, and over the sounds of metal thudding into flesh and bone there came the distant sounds of singing from around the campfire.

“Hang down your head, Tom Dooley,

Poor boy, you’re going--to--die--"

Pages 16-20

Often there were particular stories that were told over and over, stories that had become part of the folklore of the town, part of the history. In Crystal Lake, it was the story of “Camp Blood"

Camp Blood, as it came to be called was the place on the outskirts of the town, about ten miles down the country road, owned by the Christy family. For twenty-some-odd years the story had survived, passed on orally like an Indian myth. It survived because it possessed all of the ingredients that made for a legend.

It centered on a place, Camp Crystal Lake--only the locals called it Camp Blood--and its focus was violent death and mystery. The mystery was that no one had ever learned who caused the deaths or why. And it concerned a local family--the Christy’s--who owned the place and who had tried to fight the legend, to no avail. Ever since 1958, each time they tried to get the camp going again, something stopped them. Stopped them in a way that only added to the legend of Camp Blood.

Some said it began in 1957, after that young boy had drowned. His name was Jason Vorhees. Pamela Vorhees’ boy. A shy child, quiet and strange. Went swimming along out in Crystal Lake. They never found his body.

Others said it began in ‘58, when those two young camp counselors were killed. They found the horribly mutilated bodies in the barn, hacked to pieces. The girl who had found them, the murdered girl’s bunkmate, had been taken to the county hospital in a state of nervous shock. Some claimed she got better, others insisted that she was still in an institution somewhere, locked up in a padded cell and screaming about blood. The police had never solved the murders.

Theories abounded. Depending on who told the story, the murders were either committed by one of the other counselors in a fit of jealous, homicidal rage or by an escaped inmate from an insane asylum or by a Satan cult or by some deranged derelict living in the woods--still on the loose, still out there somewhere--or if you listened to crazy old Ralph, by vengeful ghosts or ravening demons or by little green men from a UFO. The story varied according to how much old Ralph had to drink, but then nobody listened to old Ralph anyway.

Old Ralph was the town geek. No small town was complete without one. Big cities had them too, more than their share, but in big cities geeks simply wandered the streets, talking to themselves and carrying all their belongings in shopping bags, sleeping in parks or down in the subways. They were ignored by a population that considered them a nuisance and didn’t really want to see them, lest they feel some spark of human pity. People in small towns noticed. Maybe no one listened to them, but at least they noticed them, which made for some kind of human interaction. Old Ralph was happier in the town of Crystal Lake then he would have been in a big city. He had no friends, except his imaginary ones and his long-suffering wife, but people noticed him and knew him.

Every now and then he’d get tanked up and hear the Call. He would mount up his old Schwinn “newsboy special," the kind of bike you don’t see anymore, with sheet metal wrapped around the top frame rail so that it looks like it has a gas tank, the kind with the big balloon tires and springs under the seat. He would ride out like Paul Revere, shouting the gospel, doing the lords work, a latter day Reverend Jonathan Edwards preaching to the sinners, a Puritan warning of an angry God. Nobody listened, but at least they heard him, and because they heard him, they called the sheriff and Officer Dorf would be send out to bring Ralph in to sleep it off.

It was a symbolic relationship. It made old Ralph feel noticed and it made Officer Dorf feel like a real policeman. He needed his big Harley-Davidson Electra Glide with the siren and the lights, he needed his spit-shined riding boots and his crash helmet with the department’s gold insignia painted on, he needed his hand-tooled gun belt, loaded down with every conceivable accessory a police officer could possibly desire, from the basket weave Bianchi leather holster to the billy club to the chromed steel handcuffs to the speed loaders to the special police Kel flashlight and the utility snap pouches, where he carried chewing gum and breath mints. He liked to use the 10-Code when he spoke on the Motorola radio, just like the cops on TV, despite the fact that there were only four officers on the Crystal Lake Police Force and there wasn’t any need to abbreviate everything using numbers instead of simple phrases in plain English. Dorf dreamed about leaving Crystal Lake and becoming a policeman in a big city like New York or Los Angeles. He felt trapped in Crystal Lake, but his police paraphernalia and his Wyatt Earp attitude helped him to live out his dream, at least a little bit.

Annie Phillips, on the other hand, felt trapped by the big city. She needed to get away every chance she got, which was mostly during summer vacations, when she took jobs as a cook at various camps. It paid a little more than just being a counselor and good cooks were always in demand. It gave her a chance to get out into the country and breathe fresh air for a few weeks. She lived for it.

She dreamed of leaving the city forever and moving to a log cabin or an A-frame house in the country, perhaps starting a small crafts business or getting a job as a cook in a resort hotel. She and Dorf might have had an interesting conversation about the pros and cons of their respective dreams, but Dorf wasn’t on hand to welcome her to Crystal Lake when she arrived. He was out cruising on the highway, looking for speeders, and all Annie had to welcome her was she hiked into town was Ed Bryant’s old dog, Winslow, who watched the pumps for Ed and barked whenever a car pulled in.

Pages 28-34

Annie opened up the door and jumped down lightly. “No sweat. Thanks a lot for the lift."

She dragged her knapsack off the front seat and set it down between her legs, then slammed the door shut. Enos pulled off with a wave, shaking his head sadly. Annie watched him drive off. She hoped he wasn’t a typical example of the folks in Crystal Lake. First crazy old Ralph, then paranoid Enos. Sometimes people in small towns were wary of outsiders. Maybe the folks in Crystal Lake were like that or maybe they just had something personal against the Christy family. In a small town, it didn’t take much. News traveled fast, everybody knew everyone else, it was hard to keep things quiet. It didn’t take much for people--or for places--to get a reputation.

An unfortunate incident like a drowning could develop into a story of a place that had been jinxed, as Enos had put it. But that has happened--when was it he said, 1957? Years ago. Assuming that it had really happened. Yet he had also said something about a couple of kids being murdered in 1958. Steve Christy hadn’t said anything about that when he hired her. Not that she could really blame him. Even if it was true, it had been a long time ago, but people were funny about some things. People who were otherwise perfectly sensible could be superstitious about things like that. That’s why if you were trying to sell a house, you didn’t tell prospective buyers someone had been murdered in it.

Enos had also mentioned something about fires. Assuming that was true as well, there was probably a perfectly logical explanation for it. Vandalism, for example. Kids fooling around at night in a place that was supposedly haunted--something like that was always good for a thrill--or maybe some of the locals had taken a hand, to make sure that the Christy family didn’t get their operation off the ground again. Who knew? Still, perhaps that was something she should ask Steve about. He seemed like a reasonable guy, straightforward and sincere. If any of these things had really happened, there was probably a perfectly good reason why he hadn’t told her. It might be difficult to get people to work there if they thought the place was jinxed. But if there was a chance they could expect some trouble from the locals, Annie wanted to know about it.

She shrugged and picked up her pack. Now she was getting paranoid. It was that easy. It didn’t take much. She started walking down the road and soon she had put Enos and crazy Ralph and their ghost stories out of her mind. It was going to be a good summer, the peaceful and quiet beauty of the country, a placid lake, campfires and songs, and who knew, maybe even a sweet, foxy hunk thrown in. And she’d be getting paid for it. Nothing like a couple of months in the woods to get your head straight before you went back to the city and to school, to noise, cold and pollution, and too many people in too small a space. One of these days, she would find just the right place to settle down. But for now, she had nothing more complicated to look forward to than cooking a few meals and kicking back at night to watch the stars or go skinny-dipping in the lake.

She had walked perhaps two or three miles when she heard the sound of a car coming up behind her. She turned and smiled and stuck out her thumb. It was a jeep, moving quickly down the road. It passed her without slowing down and she made a wry face, but then the driver hit the brakes and pulled over to the side of the road. She hitched up her pack and ran up to the jeep. Things were looking up already. She’d probably catch a ride all the way up to the camp. She opened the door, shrugged out of her pack, and tossed it in the back.

“Hi," she said, smiling at the driver as she got in. “I’m going to Camp Crystal Lake."

The driver shifted into first and the wheels spun for a moment in the loose dirt on the shoulder, then found traction, and the jeep shot forward.

“I’m going to be on the staff up at the camp." she said, trying to make pleasant conversation.

The driver remained silent.

Annie shrugged. She knew that small town people didn’t talk as much as city people, but there was no harm in trying to be friendly. “I guess I’ve always wanted to work with children," she continued. “I hate it when people call them ‘kids.’ Sounds like little goats." She grinned.

No reaction from the driver.

“Anyway, when you’ve got a dream as long as I have, I guess you’ll do anything," she said.

The driver didn’t ask about her dream, so Annie just decided to shut up and watch the scenery.

It went by at quite a rapid clip. God, she thought, first you get some crazy old coot who tells you that you’re going to die, then you get some paranoid redneck who wants you to quit your job and go back where you came from. And now this silent treatment. Maybe she shouldn’t have said anything about Camp Crystal Lake. Maybe she should have just waited until they got to the road leading to the camp and said, “You can let me out right here." Maybe the people in town of Crystal Lake really did have something against Steve Christy.

She decided to be grateful for small favors. At least she was getting a ride. And at the speed they were going, they’d be there soon. She wouldn’t have to put up with the silent treatment for much longer.

They were driving well over the speed limit. She watched the trees whip by, and then a small road leading off on a diagonal, with a signpost that said, “Camp Crystal Lake." She turned and watched it recede.

“Hey, wasn’t that the road for Camp Crystal Lake back there?" she said.

No response from the driver. The jeep didn’t slow down.

She glanced back out the window, then started at the driver nervously. “Uh…think we’d better stop. You can let me out right here."

The jeep did not slow down.

“Please?" said Annie, starting to feel a little frightened.

The jeep sped up.

“Please, stop!"

The driver didn’t even look at her.

“Please! Stop!"

Now the driver looked. Annie panicked at the expression of utter loathing and cold fury in those eyes.

She fumbled for the door handle, forgetting all about her backpack, and managed to get the door open. The wind whistled past her as she struggled to push it open. They had to be doing at least sixty. She jumped.

She cried out as she struck the dirt shoulder of the road and rolled down into a ditch. For a moment, she lay stunned, feeling the shock of the impact and the sudden pain shooting up her leg.

The tires screeched as the driver hit the brakes. The engine revved as the jeep was shifted into reverse. Then Annie heard it backing up. She had no idea what the driver was going to do and she had no intention of waiting around to find out.

She struggled to her feet, wincing with pain. Her leg would barely support her. She saw the jeep approaching quickly and she turned and limped off into the woods, trying to get out of sight. As she hobbled into the shelter of the trees, she heard the jeep stop and the door slam.

Fear sent adrenaline coursing through her and she half ran, half stumbled through the bushes, ignoring the branches that struck her face, not knowing where she was going, just fleeing in directionless panic, trying to put as much distance between herself and her pursuer as possible. She whimpered as she staggered ahead, both from fear and pain, and imagined she heard a crashing through the brush behind her. She tried to speed up and fell, her leg buckling beneath her. She sobbed for breath, biting her lip to keep from crying out.

She glanced quickly all around her.

Everything was quiet.

She was afraid to move. Afraid to make the slightest sound.

She strained to listen.

There! A footstep!

Where? Where was it coming from? She had lost all sense of direction. She turned…and saw a pair of legs right in front of her. She looked up slowly and saw the knife.

“No," she whimpered, shaking her head, her eyes wide with fear. “Please, no!"

She backed away, scuttling in the leaves, unable to take her eyes off the keen blade. She came up against a tree.

Get up, her mind screamed. Get up and run! Run!

She struggled to her feet, using the tree for support, her breath coming in quick gasps. “No, please, no…"

All she could see was the knife, shining brightly, coming closer…

She screamed and felt a searing, white-hot pain as the blade slashed across her throat, opening a deep gash that spouted blood as the knife sliced through her trachea, severing her jugular vein. Then she couldn’t scream anymore as blood filled her lungs and her vision was blurred by a red mist.

Pages 35-46

As Annie’s life was ending in the woods about three-quarters of a mile from Camp Crystal Lake, Ned Rubenstein felt that his was just beginning. He turned right at the intersection of the crossroads and gunned his brand-new Chevy pickup down the country road. The cab was filled with bluegrass music from the tape deck and the interior still had that new car smell. The truck was a present from his father for having made the honor roll every year since he had started high school. Ned was always goofing off and his father had made the promise easily, never dreaming Ned could do it, but he had underestimated him.

The deal was that if Ned buckled down and worked hard for four years, he’d get a new car for graduation and be allowed to attend the college of his choice. That was all it took, a little motivation. And it hadn’t been that difficult to do. His reward had been a brand-new red Chevy pickup with a white camper on top and a killer sound system and, in the fall, he’d be heading out to California to start school at UCLA.

He couldn’t wait. He was already dreaming of the beach at Malibu, thinking about the girls he’d meet and the connections he would make in UCLA’s film program. He’d already had half a dozen T-shirts made, all different colors, all bearing the legend, “Why grow up when you can make movies?" Add a couple pairs of jeans and some new Reeboks and there was his college wardrobe. Now all he had to do was kick back for a few lazy weeks in the woods, take some little kids on nature hikes and teach them swimming and archery, and then mellow out around the campfire after they had gone to bed, drink a few beers, and smoke a joint or two while he dreamed California dreams. Everything was great. All it would take to make it a perfect summer would be meeting some foxy girl up at the camp.

Jack, on the other hand, wasn’t taking any chances. He had brought his own. He and Marcie were sitting in the back of the big cab, making out. They had been inseparable all through their senior year and they had signed up as counselors together so they could spend the summer with each other before going off to different schools. Outwardly, they both talked about keeping their relationship going, but, realistically, they both realized the odds of remaining a couple were slim once they’d started college in different states and started meeting different people.

Consequently, there was a last minute urgency about them. They were like a bomb getting ready to go off.

Ned glanced up in the review mirror. “Hey, Marcie?"

She broke off their kiss long enough to acknowledge his presence. “What?"

Ned grinned. “You think there’ll be other gorgeous women at Camp Crystal Lake, besides yourself?"

Marcie laughed. “Is sex all you ever think about, Ned?"

“Hey, no. No, absolutely not!"

“Ha!" Jack made a face.

“Sometimes I just think about kissing women," Ned said. He couldn’t resist rubbing it in a little. He knew that Jack and Marcie hadn’t made it yet. Jack had confessed as much to him one night over a few beers. It drove him crazy. Marcie apparently kissed like a nuclear reactor melting down, but always drew the line at having sex. Jack claimed it was one of the things he really liked about her. Ned remembered being brought up short that that peculiar comment.

“Now wait a minute," he had said, “let me get this straight. It’s driving you crazy that she won’t sleep with you, and at the same time you say the fact that she won’t have sex with you is one of the things you like about her?"

Jack had taken a long swig of beer and grinned. “Yeah, I guess it does sound sort of weird, doesn’t it? But think about it. If a guy wants to get laid, there are a lot of girls around who wouldn’t mind at all. But I don’t want to pressure Marcie. If you love somebody, you don’t pressure them. Love is about trust, not lust."

“Yeah, but it sounds to me as if you’re suffering from a bad case of both," said Ned. “Love and lust."

Look, I love Marcie, all right?" said Jack. “And if you love somebody, I mean if you really love them and you’re not just bullshitting yourself, you don’t try to jump their bones just because you’re horny. If that’s the bottom line, then you’re not making love, man, you’re just using someone else to get your rocks off. If you’re that cheap and sleazy, you might as well whack off. At least you don’t have to buy your right hand dinner. If you’re doing that to someone else, you’re lying to them, man. And chances are, if it’s that easy, they’re probably doing it to you. That’s not being in love, that’s just being selfish."

“God damn, Jack," Ned said, grinning. “You’re a romantic."

“So? You think that’s funny? What the hell is wrong with being romantic? Maybe if more people were romantic, they’d stay together longer."

Well, that’s what you say," said Ned. “But is it what you really believe? This is going to be your last summer together, man. It’s gotta be now or never."

“I know," said Jack, staring miserably into his beer. “I know; you don’t have to tell me."

They pulled off onto the dirt road marked with a new sign that read CAMP CRYSTAL LAKE. Ned slowed down and followed the winding dirt road through the trees until they came to a larger sign saying, WELCOME TO CAMP CRYSTAL LAKE, EST. 1935. A lean, shirtless man with eyeglasses and a mustache was swinging an ax, leaning into it as he chopped at the roots of a large tree stump. Ned pulled over and parked.

“Hey, you want to give me a hand over here?" the man yelled as they got out of the truck.

“Sure," said Jack.

The shirtless man turned and called out toward one of the cabins. “Alice!"

A pretty young blond woman came out, carrying a broom.

“I want to get this tree stump out," the man said to them. “Get on this side. You pull on this side and I’ll pry. On three, okay? Alice?"

“Coming," shouted the blonde, hurrying over to them.

He counted off and they all put their backs into it. The stump resisted for a moment, then it went over and both Jack and Ned stumbled back slightly as it gave way.

“That’s great," said the shirtless man, taking off his work gloves. He offered Jack his hand. “I’m Steve Christy."

“Jack Kendall. This is Marcie Gilchrist."

“Hi, there."

“Ned Rubenstein."

“Welcome to Camp Crystal Lake," said Steve. “This is Alice."

“Hi," the blond woman said, smiling at them. “Ah, Steve, Cabin B’s all ready."

“Oh, good," said Steve. “Where’s Bill? Has he finished cleaning out the boathouse yet?"

“I don’t know," said Alice. “I haven’t seen him in the past half hour."

“Oh." said Steve. “I wanted him to start painting right away."

Ned glanced at Jack and Marcie. What the hell was the rush?

“Well, what about Brenda?" Steve said?

“You told her to go set up the archery range," said Alice.

“No, no," said Steve, “I’d rather she paint." He turned to face the others. “Well, come on. Let’s go." He clapped his hands together and rushed off somewhere like a man trying to get ten things done at once.

Ned looked at Alice with bewilderment. “I thought we had two weeks," he said.

Alice laughed. “Come on, I’ll show you where you can stow your gear and get changed."

They barely had time to put on shorts and sneakers when Steve Christy came back, detailing jobs alike a drill sergeant in boot camp. He seemed hyper and nervous, anxious to get everything done right away, and as fast as they worked, he thought of new things that needed to be done immediately. He kept pulling out an inventory list he had made up of items from the hardware store in town; it seemed he’d brought out their entire stock. Ned began to feel that by the time the kids arrived, they’d all be utterly exhausted.

They swept out cabins and replaced door hinges, painted trim and put new putty around the windows, installed signed on buildings with drills and wood screws, chopped firewood, installed new oar locks on the rowboats, cleaned the bathrooms, and generally ran around like squirrels storing away nuts for the winter. And they had just arrived.

Had they known about the history of the camp and Steve Christy’s personal problems, they might have understood his anxiety. As it was, they were having reservations about the laid-back summer they’d been hoping for. If this was any indication of what they could expect, it could turn out to be a real hassle. Who the hell needed a camp director who thought he was a troop commander? Still, the work needed to be done and setting up a camp properly always took a lot more time and effort than running it did. The sooner they got it done, the sooner they’d be able to relax. For the time being, they decided to give Steve Christy the benefit of the doubt. But he did seem awful nervous.

They broke for lunch--sandwiches and chips--which Alice threw together because the new cook hadn’t arrived yet. Steve took yet another trip into town to pick up more supplies. It hardly seemed possible that it was only lunchtime, considering all the work they’d done, but they were making rapid progress. Even Steve started to relax a bit when he saw how things were going.

He set down a box and helped Alice balance a rain gutter she was attaching to the roof. “Here, let me give you a hand with that."

“Thanks," she said, speaking around the nails in her mouth. She needed three hands to balance the gutter, keep her own balance on the ladder, and hammer in the nails. They were all getting tired.

“Got it?"

“I got it."

Alice drove the nails in, climbed down, and moved the ladder. Steve picked up a sketchpad she’d left lying on the deck in front of the cabin. He flipped the pages slowly. They were drawings she had made of the campsite, of the lakeshore, and of him.

“You draw very well," he said.

“Thanks," she said. “I wish I had more time to do it." Take the hint, Steve, she thought. For God’s sake, relax a little.

“When did you do this?" Steve said.

“Last night."

She started hammering nails again. Steve stared at the drawing she had made of him.

“Do I really look like that?"

She glanced over her shoulder. “You did last night," she said. She took the remaining nails and pounded them in, then climbed down the ladder.

“You’ve got talent," said Steve. The conversation seemed awkward somehow, after she’d brought up last night.

They’d been alone and had done a lot of talking, but nothing had been resolved. She didn’t really understand his need to go through with this. As far as she could see, the camp was nothing more than a white elephant. Steve had a real problem with it and she had problems of her own, of which Steve was one. He insisted on getting the camp started up again, fixing it all up, and making it a making a going concern. He said it was to prove that the story about the place being jinxed was nonsense, that once the camp was all fixed up and they’d had a good season, it would be easier to sell it. But she had the feeling it was much more than that. He had to prove something to himself, as well. Prove not only that there was no curse on the camp, but that were was no curse on the Christy family, either. The place had ruined his father and he was obsessed with the idea of making a go of it, of succeeding where his father had failed.

“This really isn’t your cup of tea, is it?" Steve said.

He’d been hoping that she could get caught up in the spirit of the whole thing, that working together would help to bring them closer, but she was only going through the motions. Maybe that was the problem with their relationship as well. They were only going through the motions. And Alice had other options.

She signed and said nothing.

“Want to talk about it?"

“It’s just a problem I’m having," she said. “Nothing personal," she added ironically.

He took a deep breath. “You want to leave?"

“I don’t know," she said. “I may have to go back to California to straighten something out."

“Come on," said Steve. “Give me another chance. Stay a week. Help get the place ready. By Friday, if you’re still not happy, I’ll put you on the bus myself."

“All right, Friday," she said. “I’ll give it a week."

“Thanks, Alice." He started to turn away, then stopped, looked over his shoulder, and said, “Oh, do me a favor? Check with Bill and see if we need anymore paint."

She started after him in disbelief as he walked away, carrying the box from the hardware store. She was seriously beginning to wonder why he wanted her to stay. Was it because they needed to see if they could work things out between them or was it just because he could use another warm body to get the camp ready? Well, she had given him a week. If he didn’t come down to earth and get his head straight by next Friday, she’d be on that bus.

She turned and started walking through the trees down toward the dock. She simply couldn’t understand why this whole thing was so important. It was only real estate, after all. Granted, it wasn’t exactly a booming area, but would it really make that much difference if there was a summer camp established on the property? If Steve wanted to sell it, why didn’t he just put it on the market and let it go at that? He had argued that the summer camp would make a difference, a big difference, that it would turn a basically worthless piece of property into an income-producing property, which would make it that much easier to sell. They had argued about it. She couldn’t see his point. How could lakefront property be worthless?

“It isn’t about whether or not it’s income-producing property," she had said. “It’s about this obsession of yours with this Christy family curse nonsense. That’s what it’s really about, isn’t it?"

“Don’t be ridiculous," said Steve. “You know perfectly well there isn’t any curse--"

“That’s right," she said, “I know it perfectly well and you know it perfectly well. So why isn’t that enough? Why do you have to prove it to the people in this town? Who cares what they think?"

“It isn’t that," Steve had said. “You don’t really understand--"

“So explain it to me, then," she demanded. “I mean, what is it, you want to stay in Crystal Lake for the rest of your life and run a summer camp two months out of the year? For heaven’s sake, Steve, write it off. Put it up for sale with an agent, cut your losses, and let’s go do something with our lives!"

But it wasn’t all that simple. Steve had unfinished business and he wanted her to wait and help him finish it. Meanwhile, she had unfinished business of her own back in L.A. And she wasn’t all that certain she wanted to finish it. Maybe it was her business here, with Steve, she should be finishing. In any case, she had a week in which to make up her mind. Why did relationships have to be so goddamned complicated?

“Bill?" She called to the young man working by the dock. “Steve wants to know if we need more paint."

“The paint’s all right," Bill said. “I think we’re going to need some more thinner, though."

“Okay, I’ll tell him." She turned to go.

“Alice?"

“Yeah?"

“Did the others show up?"

“Yeah," she said, “everybody except that girl who was supposed to handle the kitchen. Annie."

Bill wiped his forehead with the back of his hand. “You think we’re gonna last all summer?" he said, grinning.

“I don’t know if I’m going to last all week." She signed.

Bill laughed, but she didn’t. She wasn’t joking.

Pages 50-53

Jack and Marcie couldn’t hold it in any longer. They both started laughing and Brenda realized that she’d been had. Jack and Marcie, who both knew Ned from school, were used to him doing things like that. He could tell the most outrageous stories with a straight face, just making them up as he went along, seeing how far he could push it before people realized he was pulling their legs. He was a real screwball that way, always goofing off, but the work that morning had gone a lot easier with him around keeping things light.

It hadn’t taken him long to realize that Brenda was a sucker for a straight face and an outrageous line and she had immediately become his favorite mark, but she didn’t really mind. He made her laugh. It was a big improvement over most of the guys she’d known who were always concerned with coming on strong and cool to impress her. Neddy’s sense of humor impressed her much more than some guy cruising her like a macho jerk. She’d had more than her share of those.

She opened the door of the prefab storage shed and took out one of the straw archery butts. Earlier that morning, she’d slipped the new targets on over the straw butts and screwed the tripods together, so now all she had to do was carry the targets onto the range. She picked up the target. It was awkward to carry, through, not very heavy. She walked out to the range with it, where she had already set up the tripods. She hung the target on the tripod and stepped back from it a pace, brushing a few stray pieces of straw off her shirt. Suddenly an arrow hissed right past her and thudded into the bull’s-eye of the target, missing her only by about a food.

She gasped and turned to see Ned standing a short distance away, holding a bow and several arrows.

“Ta-da!" he sang out, giving her a little bow.

She stared at him with disbelief. “Are you crazy?"

“Wanna see my trick shot?" he asked, grinning and fitting two arrows to the bow. “Its even better."

“I don’t believe you!"

He dropped his lip in a Bogart sneer. “You know, you’re beautiful when you’re angry, sweetheart."

“Yeah?"

“Yeah," he replied.

“Did you come here to help me or to scare me to death?" She grabbed the arrow he had shot and went after him with it.

He laughed, retreating from her in mock terror.

“Ned, if you do that again, I’m going to tack you up on the wall to dry!"

“God, I love it when you talk sexy!" He laughed.

She gave up. She just couldn’t stay mad at him. Between the cornball lines and the ridiculous delivery, there was something about him that simply got to her. She didn’t know what the hell it was. He was like an unruly little kid. She wanted to grab him, pull down his pants, and spank him. Pretty kinky, Bren, she thought. Either that or the guy’s bringing out your maternal instincts. Watch out. Could be trouble. The guys who were really dangerous were the ones who could sneak in past your defenses. And Ned was already halfway there. She felt strongly attracted to him in spite of herself.

He helped her finish hanging the targets and they went back to the cabins to change into their bathing suits and finish working on the dock. Ned kept them all in stitches, doing his impression of Steve Christy as the camp commandant, waving his arms around and barking out orders as they pushed the last piece of the dock into the water and secured it.

Pages 59-61

Back inside her cabin, Alice stripped off her bathing suit and slipped into a robe. Steve still hasn’t returned from town. So far, he’d spent the whole day running in every direction at once. He seemed more concerned with how things were going for the camp than with how things were going for them. Give me a week, he’d said. She wondered if a week would actually change anything. What could happen in a week? Well, maybe a lot could happen in a week, if they really had a chance to talk, but then they’d had a chance last night and nothing had been settled.

She looked around at the cabin, figuring she could take it for another week. It really wasn’t all that bad, but she could think of lots of places she’d rather be. Maybe even California. But there were problems there, as well. Two men in her life, both nice men, but both with their own agendas to consider. Neither of them was willing to give up his own interests for hers, but each expected her to give up interests for his sake. She wondered if she wouldn’t be better off forgetting about both of them. But it wasn’t all that easy. Nice men were hard to find and relationships were complicated. She cared about them both. John and Steve were waiting for her to make a choice. The problem was she didn’t know how to choose.

She brushed her hair and went over to the dresser, taking out some fresh underwear, a T-shirt, and a clean pair of jeans. The trouble was, she wasn’t sure what she really wanted. She didn’t like the pressure. She couldn’t think straight. Only one thing was clear; she wasn’t about to settle down in the town of Crystal Lake. When Steve had spoken to her about the camp, he had talked about it as a piece of property he had inherited, an investment, not as a business he actually planned to run himself. Nor did she expect to find herself drawn to it. She subsequently realized that Camp Crystal Lake was an albatross around Steve’s neck. Somehow, he seemed to feel that it was something he had to atone for.

The camp had been his father’s downfall. It had ruined him. There had been problems. She knew that a little boy had died--Steve didn’t like to talk about it, he wouldn’t elaborate--and the following year, something terrible had happened, an accident, Steve said, but the talk in town didn’t sound as if whatever happened had been an accident. But what did they call the place Camp Blood? One of the other kids--Ned? Or was it Bill?--had mentioned some killings that had occurred here. She wanted to ask Steve about it, but he was very sensitive about the subject. She knew the moment she brought it up, he’d overreact. She thought it would probably help to talk about it, but it was an extremely sore subject with him.

She sighed. How can you hope to have a relationship with someone who avoids things? You can’t solve problems by pretending they aren’t there. And the camp was a real problem with Steve. He was obsessed with making it a success. If he devoted as much energy to their relationship, maybe she wouldn’t be thinking of going back to California. Part of her wanted to leave and just be by herself for awhile, to think things out, and part of her kept hoping he’d give her more of a reason to stay.

As she shut the drawer, she felt something smooth brush by her foot. She jerked it back and looked down to see a large black snake slithering underneath the dresser. She jumped back and screamed.

“Bill!"

Pages 85-89

Alice set the open beers on the table, then sat down and lit up a joint, inhaling deeply.

“I’m not going to pass Go without a glow." She giggled.

“Brenda laughed. “We’ve already rolled for you. You’re going last, okay? And Community Chest can’t give you back your clothes."

She rolled the dice.

“Double sixes! I get to roll again:"

Bill sipped his beer and glanced at Alice. “I think we’re being hustled."

“I think you’re right," said Alice, leaning back in her chair and taking another toke before passing the joint to Bill.

Steve wouldn’t approve of this, she thought. If he came in now, he’d put a stop to it and give them all a lecture on responsibility. She signed. He’d think all this was juvenile, silly. But it wouldn’t hurt him to be a little silly and juvenile on occasion. Even a little irresponsible. If he kept pushing himself like this, he’d wind up with an ulcer and she certainly wouldn’t be around to see it. She’d be dozing in the California sun.

He’d been so different when she met him. Gentle, compassionate, attentive. Or had she only seen what she had wanted to see? It wasn’t that he was unkind of that he took her for granted; it was just that he was too wrapped up in his plans, to the point of obsession. He simply wasn’t able to see what was really happening around him.

Perhaps it was her fault. Perhaps she should have seen it coming. Maybe there was something about her that led her to make the same mistakes with men, over and over. She had been vulnerable when she met him, trying to get over the breakup of a relationship that hasn’t been going anywhere--she had told John that she needed time away from him for a while to thin, time to herself--and then along came Steve, who seemed so very different, so much more relaxed and easygoing.

And now she was stuck in the same rut all over again. It was one thing to have plans, to have ambition, goals, but it was something else entirely when those goals and ambitions took over and blocked out everything else. Her father had been like that and she had seen what it had done to her mother.

Her father had been a commodities broker. He had started out with nothing, determined to make a good life for his family. He had worked like a dog, putting in long hours at the office and bringing work home with him, always on the telephone, always with his nose stuck in the Wall Street Journal, always caught up in his dream. There was nothing wrong with pursuing a dream, she thought. There was nothing wrong with planning for the future. But you couldn’t live in the future. You had to take time out to appreciate the present.

Then her father started spending more time at the office than at home. Breakfast with the family became gulped coffee while he scanned the market reports. Conversations over dinner, on those rare occasions when he came home in time for it, because absent grunts and nods while his mind was somewhere else--on work, always the work. He never spoke of anything else. Alice had watched her mother becoming more and more withdrawn, more and more alienated from her husbands world.

There was never any time for vacations. There was no time for going out to dinner or the movies, or playing with the kids on weekends, or just curling up in front of the fireplace with a glass of wine and a good book. Occasionally, there had been time for arguments, with her mother pleading that he shouldn’t work so hard and her father insisting that he was doing it all for them, so that they could have a better life. It was always the dream of the better life, never the thought that life might just be good enough the way it was if he could only take the time out to enjoy it. But he couldn’t seem to find the time. That time kept drifting into the future, and finally, there was no time left.

Like a clock with a mainspring wound too tight, her father had finally snapped. He had died of a coronary. They had found him slumped over his office desk, a telephone receiver in either hand. He had literally worked himself to death and his heart had burst.

Alice was never going to go through anything like that again. She didn’t want any part of men who became so caught in their plans and ambitions that she wound up being pushed aside. You don’t work for a relationship, she thought, you work at it. And that meant communicating. It meant sharing. It meant not putting things off until some other time when it might be more convenient. That time might never arrive.

When Steve came back, she was going to have to confront him with it. Maybe if she explained to him why she felt the way she did, he’d understand. Maybe then he’d open up and talk about it, instead of avoiding the subject as he always did.

It was almost as if he was afraid to talk about it. She had seen the curious change come over him as they had driven up to the lake, she had seen him grow tense and moody. As they approached the camp, he had stopped the jeep at the entrance, his mouth a thin line as he simply sat and stared through the windshield at the empty cabins on the lakeshore, like an old soldier revisiting a battlefield.

“What is it, Steve?" she had asked him?

For a long moment, he said nothing.

“Steve?"

He had blinked, as if coming out of a daze, and turned to look at her, a forced smile on his face.

“Nothing," he said. “Just thinking about all the work we have to do, that’s all."

But that wasn’t all. She knew there was something else, something he wouldn’t tell her. There was a sense of desperation about him, as if he was frightened of something. What was he so afraid of? He acted as if it were all a mater of life and death.

Pages 91-96

Jack lit up a joint and waved the match out, flicking it onto the floor. He drew the smoke in deeply and exhaled as he lay back on the bed. He thought about Marcie. He wondered if she was taking birth control pills. He wondered why he hadn’t wondered about that before. It was a little late to ask himself that now. Suppose she got pregnant?

Surely she was on the pill. Wasn’t she? She wouldn’t have sex if she weren’t on the pill, thought Jack. But then, on the other hand, he’d had sex and he hadn’t used a condom. Why wasn’t that the same? Wasn’t it being sexist to expect her to take full responsibility for them both being protected? Was it fair to justify it by telling himself that he got carried away, what with the thunder and the lightning getting her excited and the dark, romantic cabin and being all alone out in the woods, her being so near and touching him and looking up at him like that?

He reassured himself that he had never pressured her, that she had made the choice. But what if she got pregnant? What then? They had never discussed that possibility. Would she consider having an abortion? How did she feel about that? Jack didn’t even know how he felt about that. On one hand, it was her body and, ultimately, her choice…but on the other hand, he would have been a part of it as well. It wasn’t something they had ever discussed.

Suppose she got pregnant and decided to have the baby? What then? Marriage? Okay, he loved her, no question about that, and he also believed in doing the right thing. He could probably get a transfer to her school…well, come to think of it, she probably wouldn’t be able to go to school, certainly not for a while, and he’d have to get a job, they’d both probably have to get jobs…Could they balance school and jobs and caring for the baby? Day care was expensive, so were diapers, clothes, baby food, medical insurance. . . . And all right, maybe there wasn’t any question that they loved each other, but were they ready to take a step that big?

How come we never talked about this shit before? Jack wondered. It wasn’t that he felt guilty about what they had done; there wasn’t anything wrong with that. They loved each other, they had waiting until the time seemed right. It wasn’t as if he had just torn off a piece only for the sake of getting laid. This was Marcie, someone he really cared about. But if you really care about someone, Jack thought, you communicated with them; you find out how they feel about things; you talk things out.

Why was it so difficult to talk about sex? Oh, it wasn’t hard at all to talk about it with other guys, like Neddy, but why did it seem awkward to sit down and just discuss it, in a non-threatening way with a girl you cared about? For that matter, he thought, why couldn’t a bunch of us just sit down together and talk about it, just between ourselves, a nice, friendly, loose discussion, find out how we feel about things, bounce ideas off each other?

He imagined himself walking up to the other guys some night, like, maybe tomorrow night, when they were gathered around a campfire, having a few beers, maybe smoking a few, and saying, “Hey, what do you say we talk about sex?"

Of course, they’d probably laugh. So would he if Neddy had said something like that, but after they had laughed--and laughing was good to break the tension--he could tell them he was serious, that he wasn’t saying that they should talk about, you know, doing it, but how they really felt about it, what concerns they had about relationships and things like that. Why couldn’t they talk about things like that in a serious, sharing sort of way?

Right then he decided he was going to have a long talk with Marcie that night. That instead of just jumping back into bed with each other and picking up where they’d left off (much as he wanted to do it again) they were going to talk first, really talk and find out how they felt about things, about their plans and how they truly felt about each other. You shouldn’t just let you feelings take control, he thought. They’d just been physically intimate with one another and it was past time they got mentally intimate as well.

Maybe nothing would change. There had been a strong sense of inevitability about this, ever since they knew they would be moving on to different schools, meeting new people, and probably forming new relationships--the tension had been there. It was something they both felt, but they’d never really talked about it. It seemed they both knew it would happen, and it also seemed they both knew it would happen sometime this summer. It was a large part of why they’d decided to take jobs at the camp together, so they could get away and be by themselves before their paths took them in different directions. Deep down, maybe they both knew that after this summer it would be over for them. It didn’t really have to be, but it would be hard to keep things going with all the changes that were coming. They had to go for it while there was still time.

But they had never talked.

“You gotta go for it," on of Jack’s friends at school had said, when they discussed their girlfriends one evening in the locker room after basketball practice. “I mean, you gotta ask yourself," Jack’s friend had said, “what are you waiting for?"

“I’m waiting for it to be right," Jack replied.

“Yeah, you could wait forever that way," warned his friend.

“I don’t want to pressure Marcie," Jack said.

“Did it ever occur to you that maybe she’s waiting for you to make the move?"

“Yeah, sure, I thought about it, but--"

“But what? You’re gonna be going to State and Marcie’s gonna be going to Boston. You think she’s not gonna meet new guys up there? You think you’re not gonna meet new girls?"

“Well, if that’s the way it’s going to be," said Jack, “then maybe we shouldn’t do it, you know? I mean, if it’s not gonna lead to anything--"

“Who says its got to lead to something? What are you sayin’, you want to get married, for Christ’s sake? You want to wind up sitting all alone in your college dorm some night, thinking about what might have been? All right, so you’re waiting for her, I can understand that, I guess, but you ever think that maybe she might be getting tired of waiting for you? You gotta go for it, man. Life’s too short.

Jack took another long drag on the joint. Maybe his friend was right. Well, the tension was over now. They’d done it and it had been great, better than he could have imagined, and he didn’t feel sorry that they’d done it--no sorrier than he felt that they’d waited--but doing it had been the easy part. They’d opened their bodies up to each other, but that was only part of it. Maybe it was corny, but he felt it was time for them to open their hearts as well. Way past time. You gotta go for that, Jack thought, if you really want making love to mean something, if you want it to me making love, rather than just screwing. He felt really close to Marcie now and he wanted to feel closer. They had to talk about it. Life was too short.

Something dripped down onto his forehead.

What the hell, he thought, don’t tell me that dam roof leaks. . . But Neddy’s mattress was directly above him, not the roof. He wiped his forehead and squinted at his fingers in the light from the flickering candle.

His fingers were streaked with red.

Pages 102-106

She thought of Jack, of his slim, strong body, the feel of his warm skin, his lips on hers, the way he felt inside her. God, she had wanted him so much! All the time they’d known each other, every time they’d almost done it, come so close that they had both ached with the need for one another, all the times she’d pulled back when she really wanted to tear his clothes off and attack him.

She wondered if she had been his first. He certainly hadn’t acted as if he was uncertain or inexperienced. But then, would a guy admit if he was? No, she guessed that Jack probably had girls before, and that the fact that he hadn’t rushed her made it that much more special. She wondered if he knew she was on the pill. He’d never asked her, but he probably assumed she was, figuring she would’ve said something if she wasn’t, although she knew girls who didn’t use anything, but didn’t let that stop them. Stupid. She wondered if he had through she was a virgin.

In fact, she wasn’t, though she had not been on the pill when she had done it the first time. It hadn’t been smart. And it certainly hadn’t been special. It was long before she met Jack. She had only been fifteen. The experience left much to be desired.

Some of her girlfriends had talked about “saving it" for when they got married, or at least for the “right guy," but that idea had always bothered her. How did you know? How did you know when it was “right"? How could you know if it was really good with someone that you cared about if you had no basis for comparison? And she had no desire to wait until she got married to have sex. Sex was sex and love was love and the ideal situation, of course, was when they went together, but you had to know how to tell the difference between the two. Even so, just because you loved someone was no reason to marry them. It might be a reason to have sex, but it took more than desire to make a marriage or even a relationship. It seemed like every second or third marriage nowadays was ending in divorce and she didn’t want to be part of those statistics.

The first time had been okay, but that was about all she could say for it. Afterward, it hadn’t seemed like a very big deal at all. And that was probably why she had felt so disappointed. It should have been a big deal. Some of her older, more experienced girlfriends had told her about orgasms, about what they felt like, about how incredible it was, but she hadn’t had one that first time. She had gotten we, but she knew that wasn’t it. She remembered thinking, Okay, so that’s what it’s like; well, now I know. She knew there had to be much more to it.

She started taking the pill eight months ago. She had frankly expected to have sex with Jack long before this, but she always found herself pulling back at the last moment. It probably wasn’t fair to him to get him so hot all those times and then stop just before they passed the point of no return, but then it wasn’t just a case of her getting him all hot and bothered. It worked both ways. She felt the frustration, too. She cared for him, she cared for him a lot, but she didn’t want to give in to the feelings of the moment only to lie there afterward, thinking to herself, Okay so that’s what it’s like with him; Well, now I know.

Hell, if a girl just wanted to get laid, it was the easiest thing in the world, especially if she was pretty and had nice tits. She just picked up a fake ID, teamed up with a girlfriend she could trust, and hit some bar where she could be sure you wouldn’t run into anyone from school. Or she could go to any one of a million places were you could get hit on my older guys. Christ, it happened all the time. You got hit on in supermarkets, for God’s sake, and in record stores and just walking down the street. And these days, you didn’t even have to wait to get hit on; you could pick out some guy who looked nice, someone who wasn’t an obvious sleaze, and you could make the moves yourself. She knew some girls who did just that, who even made a point of going after married men on the theory they wouldn’t hassle you because they had much more to lose. But that wasn’t what she wanted. She wanted more. Much more.

She didn’t want a short interlude of heavy breathing and temporary pleasure. She wouldn’t settle for just “feeling good." She remembered, after that first time, talking about it with her more experienced girlfriend, who had said, “God, wasn’t it great? Didn’t it just make you want to do it with every foxy guy you know?"

She had said yes, because the conversation seemed to call for it, but she hadn’t meant it. What she had wanted to say was, “Yeah, well, I guess it was sort of nice, but is that really all there is?" And, “No, it doesn’t make me want to do it with every foxy guy I know. It made me wonder if it’s any different with somebody who loves me, with somebody who wants to be inside me, not just my body."

It made me want to do it with somebody who’d carve our initials on a tree, leave behind more than a memory. A statement. We were here. We did this. We loved.

She hated to think of them being apart after this summer. She felt very close to him right now. But she wanted to feel closer, because of what they’d shared. It was funny, in a way. For as long as they’d been together, there was always that pressure, that slight tension about when it was going to happen. Not if it would happen, but when. There hadn’t been any questions in her mind about the if for quite some time. And now that it had happened, she felt a pressing need to get even closer to him, to become a part of him, especially since they were going to go their different ways after this summer.

She just wished she could peel back the layers of his mind and look inside, see and feel what he was really thinking. Have it written on the wall of her memory.

We were here. We Loved.

She thought she heard the squeak of the door opening and she pushed the stall door open and peeked out.

“Jack?"

No answer.

Pages 114-121

Steve Christy sat hunched over his coffee at the counter in the general store. It had been a long day, running herd on the counselors, trying to get everything organized, and he was sick and tired of constantly running back into town because he had forgotten something. He had wanted to make sure this would be the last trip. He didn’t particularly enjoy coming into town picking up supplies. Not that anyone gave him a hard time, but there was an edge to the way they all behaved around him. They looked at him strangely. They didn’t have to say a thing. Their eyes did all the talking.

Sandy was the only one who didn’t look at him as if he were is father’s ghost. He had lingered at the counter, enjoying a hot dinner, munching a hot slice of apple pie, and nursing his coffee, much as he used to linger over Cokes and ice cream sodas at this same counter when he was a kid and a much-younger Sandy used to flirt with him, making him feel older. She always had a smile and a friendly word or two, and if she ever said anything about the camp, she didn’t talk about it in his presence. She seemed to understand t hat it was a sore point with him and that this was something he needed to do, if for no other reason than to prove everyone wrong about Camp Crystal Lake and his father.

I’ll make a go of that damn place, he thought. I’ll make a go of it and show them what a bunch of superstitious nonsense all this stuff about “Camp Blood" is. I’ll show them they were wrong about it, just like they were wrong about my father, a man whose only curse was an incredibly pathetic run of the worst luck in the word. And it would server them right if I sold the goddamned place for a hefty profit to some real estate developer who’d come in and put up condos. He grimaced. That did not seem very likely, although Alice thought it could happen. Lakefront property, she’d said. How can lakefront property be worthless?

He’d wanted to tell her.

Tell her the real reason.

Instead, what he had told her was that it can be worthless if it’s in an area that’s economically depressed. Small towns were dying all over the country. No jobs. The agriculture industry was going down the tubes, with banks foreclosing on small farms and small-town businesses being bled dry as they lost their customers. It would take a lot more to turn things around than an occasional rock concert or music video to benefit the farmer.

Every domestic industry was being affected as the country shifted more and more to service industries and moved away from production, unable to compete with cheaper goods and labor from abroad. There had to be production. People had to get back to working with their hands. They had to have faith in themselves, in their own abilities, in the American spirit. Even the Japanese were saying that. People were buying Japanese cars because they thought they were better than American cars, that the Japanese had better production and better quality control, but even the Japanese admitted that they had learned it from America. He could remember a time when nobody would even touch anything if it said “Made in Japan." That had changed because the Japanese people had made a commitment to changing it. They had worked hard.

He had always made a point of reading about people who had started successful companies. About their beginnings. You learned how to be successful by studying successful people. Soichiro Honda had started with a small repair shop in Hamamatsu in 1928 and built it up into a factory producing piston rings, a factory that was bombed to smithereens during the war. But he hadn’t given up. After the war, he started all over again, founding the Honda Technical Research Institute. It was an impressive sounding name, but the “Institute" had actually been only a wooden shed, measuring 18 by 12 feet. Honda had bought 500 army surplus engines, hired a few workers, and stuck the engines into bicycles, connecting them to the rear wheels with a drive belt. They ran on a mixture of gasoline and turpentine and smoked like a plugged up chimney. Not much of a beginning, but look where the Honda Corporation was today.

And look at Chrysler, he thought. Look at any company where the people really cared about what they were doing and you’d see that you can turn anything around if you’re willing to work at it. Compared to some of those stores, a rundown summer camp was a joke. But then, an 18 by 12 foot wooden shed that was supposed to be a “research institute" was a joke, as well.

Sure, he could have taken the easy way out, he could have put the place up for sale, as rundown as it was, and cut his losses, as Alice had suggested.

Alice simply didn’t understand his dreams. She couldn’t appreciate the long view. She didn’t even understand the most basic elements of business. Lakefront property, to her, naturally meant it wasn’t worthless. Never mind that it was in a depressed area. Never mind that it was falling apart from neglect. Never mind that it had been plagued by bad luck, starting with a boy drowning back in 1957 and two counselors being brutally murdered in 1958 and fires set by some arsonist the year after that and one thing after another ever since, so that people now believed the place was cursed.

He had wanted to tell her the place was worthless because people believed in the curse upon it, and upon his family. They thought he was crazy to re-open the camp, to drop $25,000 of his own money to refurbish it and bring in inner city kids. Everyone in town thought drunken old Ralph was crazy, with his talk about “death curses" and “the Lord’s vengeance," but were they really any better? At least Ralph said what was on his mind. Maybe they didn’t say it out loud, like Ralph did, but they thought it. He was convinced that some of the problems his father had experienced could be traced to the residents of Crystal Lake.

He wondered, as he went around town, picking up supplies, which of the people he encountered had been the ones who set the fires, which ones had vandalized the cabins and poisoned the wells. If there was any curse upon his family, he thought, it had been put there by some of the locals, who didn’t want to see the camp succeed.

They were convinced it was an evil place and they had suited their actions to their beliefs. It was a lot like a salesman who tried to sell a product he didn’t believe in. Because he didn’t believe in it, he didn’t get behind it, and when the product--not-surprisingly--didn’t sell, he justified his own beliefs, his own failure, by saying, “See? It’s just no good. I knew it all the time."

Well, he wasn’t going to fail with the camp.

It was all he had, his legacy, his beginning. If he could make a go of it and turn it, sell it as a successful little business instead of a rundown piece of lakefront property that would be of little use to anyone except some businessmen from the city who wanted to use it as a hunting retreat, then he could make a profit on it. More importantly, he could establish himself as a real estate speculator who had taken a worthless piece of property and made something out of it. That was the sort of thing banks would look favorably upon and it would allow him to pyramid his investment, to get into something more ambitious, something he could build upon. You gotta start somewhere, he thought. You’ve gotta have a dream. Why couldn’t Alice see that?

Maybe he just couldn’t compete with that guy out in California. Maybe that was it. Maybe all Alice wanted was a reason to go back to him, because he could offer her more, and she was using the camp as that reason. If that was the case, he couldn’t fight it and he wasn’t going to try. Alice was old enough to know her own mind. She wasn’t a child, and yet sometimes she acted like one. He’d start to reveal his plans, his dreams for a better future, and he’d see her shut him out. She didn’t even want to hear it.

He had thought that if she could see the place, if she could come out and see what he had done, actually participate in the project, then she might come to appreciate what he was trying to do. But no. She didn’t really want to be there. She did her part, but her heart wasn’t in it. She seemed to be one of those “live for today" types. Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we die. If everybody thought that way, no one would ever accomplish anything.

He had lingered in the town partly because it had started raining and he wasn’t anxious to drive back in the storm. He had been hoping it would let up, but at the same time, he wasn’t looking forward to spending another night with Alice, with her trying to convince him it was all a pointless waste of time. She didn’t see the potential of the place, its possibilities for success. She saw it as a romantic retreat, a place where, apparently, she had hoped she could get him to “loosen up" and not take life so seriously.

They had each come to the camp with their individual goals in mind. He had hoped to get her interested in what he was trying to do, to get her involved so she could share his plans with him. She had hoped she could get him to walk along the lakeshore and gaze up at the stars, stop and smell the roses. Only someone had to take the time to grow and tend the roses before anyone could smell them. Alice didn’t seem to understand that and obviously wouldn’t try.

He signed and pushed away his coffee cup. Hell, what was the point? It just wasn’t going anywhere. Neither of them was going to change. Maybe she would be better off going back to California. Maybe he’d be better off as well.

“Steve," said Sandy, coming over to him. “Is there anything else you want?"

Pages 144-149

He shook his head and led her to the couch. “Why don’t you stay here and try to get some sleep? I’ll be right back."

He gently eased her down and covered her with a blanket. She stared up at him, eyes wide, lips trembling slightly. Whatever was going on, he thought, it had long since passed the joke stage. It wasn’t funny anymore. Alice was genuinely frightened, but he remained convinced that the others were behind this. The generator might have run out of gas, or they might have turned it off, just playing games. Maybe Ned put them up to this, he thought. It was just the sort of juvenile prank that he would pull, and Brenda would probably have gone along with it, but Jack and Marcie seemed to have a lot more sense than to pull something this stupid.

They had probably all gone off and smoked somewhere, got silly, and decided to play a practical joke. Hide-and-seek. Ghosts and monsters in the dark. Kid stuff. But the laughter stopped when someone got as scared as Alice did. Especially that bit with the bloody ax in Brenda’s bed. It was probably red paint; he hadn’t stopped to check. It had actually scared him a little, too. Sick, he thought. Really sick. He had half a mind to deck Neddy when he found them. And Steve wouldn’t be amused by this at all.

Unlike Alice, he knew why the people in town called the place Camp Blood. When he had first arrived, he had stopped in for breakfast at the general store in Crystal Lake and struck up a conversation with one of the locals, who had told him all about the drowning in 1957, the murders in 1958, and everything that had happened since, every time the Christy’s had tried to reopen the camp.

At first, Bill hadn’t really believed him. He had worked as a camp counselor every summer for the last five years and he’d heard every single summer-camp ghost story there was to hear. Most of them were all variations on the same theme, a tired classic told around the campfire late at night. The story of “The Hook."

There was a homicidal maniac who had killed a lot of people and had been locked up in an asylum for the criminally insane. This asylum always “just happened" to be somewhere not far from the camp. The killer, so the story went, had lost his hand, and in its place he had a steel hook. The hand was never found.

The killer had lost it somewhere nearby, in the woods, and he was obsessed with finding it. By this time, if you paced the story right and described some of the killer’s murders in particularly gruesome detail, the campers would all be sitting wide-eyed around the fire, hanging on your every word.

A lot of people thought it was just a story, you’d tell the campers. At least, the storyteller would go on to say, that’s what a couple of the counselors who worked here last year thought, until the night they sneaked off in a car, driving to a deserted country road not far away. They had parked the car beneath some trees and turned the lights out. As they were sitting there making out and listening to the radio, the girl thought she heard something just outside the car. A twig snapping. A footstep. A little scratching noise, as if someone was touching the door handle with something made of metal. . .

She got scared all of a sudden and insisted that they leave, drive off right away, and the guy she was with caught the mood from her and stared up the car and floored it, peeling out. It was only later, when they were driving back into the camp, right down that very road there--and the storyteller would point at the road leading into the camp--that they’d relaxed and started laughing about it, feeling foolish for getting so carried away and letting their imaginations get the better of them. And as they were getting out of the car, something clinked against the car door and there, hanging from the door handle, was a steel hook. . . .

And then you dropped the bombshell.

Earlier that night, you’d tell them, you had heard on the radio that the killer had escaped from the insane asylum and the state police had set up roadblocks and were combing the woods, looking for him. They had issued a warning to the people in the area to stay indoors, because the man was highly dangerous, a maniac, an animal, and he had last been seen in the vicinity of (fill in the name camp).

He’s looking for his hook, you’d tell them, in a very low voice. That very same hook that he lost last year, when he tried to kill those counselors and they’d just barely managed to escape in time. He’s convinced the hook is here, you’d continue, right here in this camp. And, in fact, those two counselors last year had left it here. It’s really been here all along and the killer knows it. He knows it’s here, he knows we have it, and he won’t rest until he gets it back.

And you’d quickly reach into your jacket and pull out a steel hook and hold it up for everyone to see. It worked best if you had taken some polish into it and really shined it up, so that it would gleam in the firelight. And it worked even better if you’d daubed some paint on the end and sprinkled it with dirt so it looked like dried blood where it had been ripped from the killer’s stump.